Unlike the “archaeology” undertaken by Thucydides, Herodotus gives a survey of cultures and customs across the known world by scribing a book whose purpose is to “show forth” the “causes” of the Persian War so that humans will not forget the deeds of great men. I believe it was Strauss who once remarked in a letter that Herodotus’s Inquiries are magnificent because the text presents both the problem and the antidote to logoi. He exoterically reaffirms the poets, by echoing the many varying tales of the war against Persia, while at the same time denying any embellishments that he cannot independently verify -an early nod to the modern process of historical/anthropological inquiry.

As is customary for the Greek mind, Herodotus praises competition -the best of men are to be held in high regard. Men like Themistocles, Phidippides, Cyrus, and Leonidas. Indeed, like Thucydides who came after him, Herodotus naturally draws his great work in sharp contrast to the earlier Homeric epics. To Herodotus and Thucydides, both independent investigators, maintaining skepticism toward the excessive poet untruth is what distinguishes their inquiry from Homeric lavish.

Is their quarrel with Homer one that is characterized by inspiring courage and greatness among the living, or rather is it to “show forth” an accurate procession of past events -great deeds that occurred without hyperbole? Or perhaps these two are not necessarily in conflict with one another -can the writer present a record of past events without the help of the poets? The inquiry into human greatness begins with the desire to seek and find greatness, and once it is found, greatness must be remembered. Greatness stands emboldened against the ever impending threat of tyranny, a tyranny that is either exemplified by the will of the tyrant that comes from the East (the Lydian Empire that upset its own customs when Caundales seals his own fate and Gyges becomes king, only for his empire to decay under the lavish leadership of Croesus, and it is then conquered by the Persians under Cyrus followed by his mad son, Cambyses, who completes the tyranny over the east by conquering Egypt, and Darius the tactician, and Xerxes, whose failures in Greece spawned the decline of the Persian War) or the Democratic Athenian tyranny of laws and endless progress. In the Aristotelian sense, the end of tyranny is “self-protection”, meaning guard or protection.

The Homeric epics wrestle with two chief concerns. The first is a poem about the city, Ilium, and its destruction. The Iliad states its subject at the outset, the wrath of Achilles and how his rage tragically sealed his fate. The warrior is necessary for the city in motion, his power is immense, and his life is gloriously remembered, but it can be tragic based on whether or not the war is won. He is swift and lacks tact. Alternatively, we are given the example of a man, Odysseus, a tactician who Homer credits with winning the war due to his cunning plan to exploit the Trojans deference for piety. Herodotus, on the other hand, examines neither of the noble types per say, but rather he surveys the varying geographies, laws, customs, and politics that form the competing ideologies of the East and the West. In paving the way for the modern ‘historical science’ Herodotus, hailing from Halicarnassus, attempts to maintain impartiality -the locus of his inquiry is neither Greek nor barbarian, and it is not a defense, or apologeia. It is rather a “showing forth” of causes for a great war so as to demonstrate human greatness. In using the Persian War, Herodotus takes the particular (the Persian War) to wonder about the universals. History in the Herodotean sense is not a mere timeline or record of events, but rather an active inquiry into human greatness. it is presented in the Greek spirit of competition as if to boldly challenge anyone to supersede his text.

Herodotus’s project subordinates the poetic for alethea, the unveiling of the true account. Like Gyges, Herodotus looks upon beautiful and noble things that are not his own, thereby transgressing the most sacred custom of antiquity. He is a traveler, a wanderer like Odysseus who sees many things that are not his own, and in looking upon things unfamiliar to a man lies the root of empire -a dangerous decline into tyranny is imminent. Recall the fate of Gyges that is played out generations later with the arrogance of Croesus in Lydia. The story of Gyges is the first full story mentioned by Herodotus, it is also repeated by Glaucon the early books of the Republic (Politeia) however it is crucially edited and misremembered by Glaucon, revealing much about his psychology but that is an inquiry for another time. Herodotus’s inquiry is perhaps more dangerous than Gyges’s transgression because Herodotus does not have political ambitions. He is not bound by nomos, or laws and customs, but rather he is in pursuit of truth and this inquiry is dangerous to the city because the city depends on untruth, knowledge of things beautiful and noble that belong to oneself. If a man travels from city to city he sees laws and customs that are entirely foreign, perhaps even values of good and evil that are incompatible with his own. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, he sees natural ‘laws’ that are the same everywhere, i.e. fire burns the same everywhere, food grows well in fertile climates, and so on, but not everyone devours devours their dead as in the case of Darius comparing the customs of the Indians and the Greeks.

However it is not my contention that Herodotus’s work permits danger to the city. By echoing the logos of the Athenians he both exoterically praises their greatness and Pindar’s claim that custom is king, while also esoterically wrestling with universal questions.

Historia for Herodotus is an inquiry into a specific moment, the Persian Wars, in order to “show forth” human greatness in opposition to tyranny, a universal question. In order to do this Herodotus presents the misleading and often contradictory stories told among and between groups. Skepticism toward the poets and rumor-mills of ideology is rife throughout his book. The closing story of the text appropriately parallels the first story told of Gyges in Lydia. The final story praises the wisdom of Cyrus in his rejection of relocating to more favorable climates for any easier life, for otherwise he falls prey to leading his empire into disarray, looking upon foreign property, securing the fate of the Persians. He instead builds an empire wherein each city practices their customs independently and is adopted under the universal subjection of Persia, the Acheamenids. However, Cyrus faces the problem of tyranny early on in rejecting the life of ease standing in opposition to his advisors who want to move to softer soiled regions where they might eat and drink better. But Cyrus decides against this for soft men and soft soil are handmaidens.

For this reading I used the impeccable Landmark edition by businessman-turned classical scholar Robert B. Strassler.

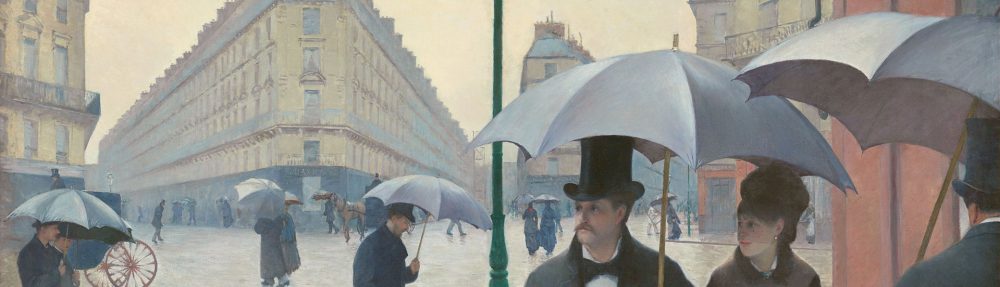

I enjoyed this post. What is the name of that artwork pictured?

LikeLike

Thank you for the comment! The painting is by William Etty in 1830 and is sometimes called the “Imprudence of Candaules”.

It is taken from the first full story recounted in Book I of Herodotus’s Histories wherein the arrogant King Caundales of the Lydians, the first seed of empire in Asia, boasts about the beauty of his unnamed wife. Therefore, he persuades his most trusted counselor, Gyges, to hide in his room to look upon his wife while she is naked, breaking Asian custom. Gyges finds himself trapped in his own tragic fate when the queen discovers this gross transgression of custom and compels Gyges to either commit regicide, and claim the Lydian Kingship for himself, or kill himself. Gyges chooses the former, sealing the fate of the Asian empires in antiquity according to Herodotus. NOTE: this story is also mistakenly recounted by Glaucon, an interlocutor of Socrates, in the early books of Plato’s Republic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for the insight, I really enjoyed it 🙂 The painting is really beautiful. Very intriguing story.

LikeLike