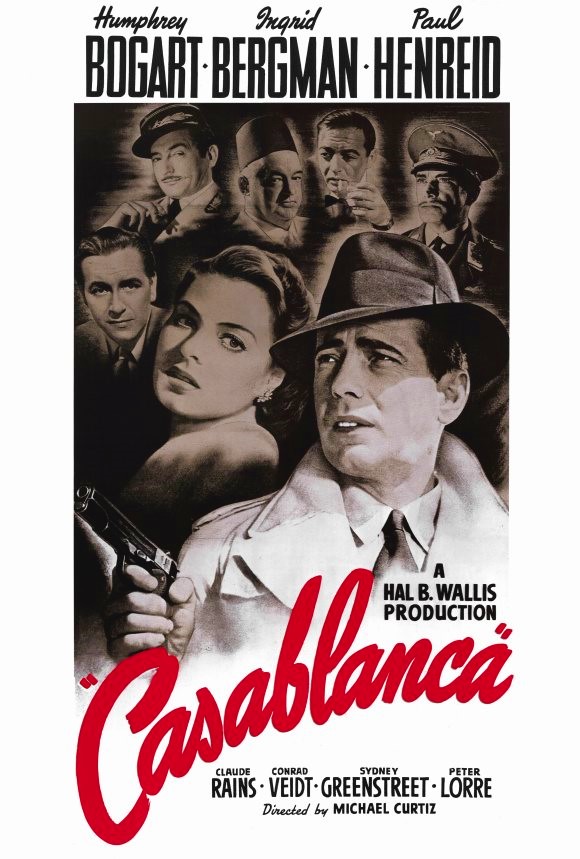

Casablanca (1942) Director: Michael Curtiz

“Here’s looking at you, kid.”

★★★★★

One of the most universally beloved films of all-time, Casablanca has sometimes been dubbed the most successful American propaganda film of the 20th century. It hit theaters on the heels of the Second World War, and somehow managed to capture the national mood of hesitance and resistance toward involvement in the war. At the time, most Americans were wary of involvement in a new European conflict –they wondered: why should we stick our necks out? Isn’t isolationism and neutrality a wise foreign policy? Public polling prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor was overwhelmingly against intervention –even as Nazi Germany invaded France and propped up its puppet Vichy government. Rushed into theaters in November 1942, Casablanca was remarkably timely, it arrived precisely when allies under General Patton managed to recapture French North Africa (including the Moroccan city of Casablanca, one of the larger metropolitan regions in neutral Morocco during the war). Screenwriters Howard Koch and the twin Epstein brothers (Julius and Philip) based Casablanca on an un-produced play “Everybody Comes to Rick’s” by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison, taking a few noted liberties here and there. The play was originally written with Clark Gable in mind as Rick, the suave café owner, but the film took a decidedly different route. Casablanca boasts an all-star cast of Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Peter Lorre and many others. It was, in many respects, a film about refugees that was also made by refugees –many of the actors in Casablanca had faced the Nazi threat abroad in one way or another. Peter Lorre fled the Nazis for Hollywood, Ingrid Bergman left Germany when she witnessed the Nazi party influence over the nation’s movie-making, Paul Henreid was dubbed an enemy of the Nazi party, Conrad Veidt fled the Nazis with his Jewish wife, and numerous other European exiles and refugees served as extras or played minor roles in the film.

The plot for Casablanca takes place a year prior to its release in December 1941. The film opens with a map of North Africa and an anonymous narrator (Lou Marcelle, uncredited) who gives us crucial context: “With the coming of the Second World War, many eyes in imprisoned Europe turned hopefully –or desperately– toward the freedom of the Americas. Lisbon became the great embarkation point, but not everybody could get to Lisbon directly. And so, a tortuous roundabout refugee trail sprang up –Paris to Marseilles, across the Mediterranean to Oran, then by train or auto or foot across the rim of Africa to Casablanca in French Morocco. Here the fortunate ones, through money or influence or luck, might obtain exit visas and scurry to Lisbon and from Lisbon to the New World, but the others wait in Casablanca… and wait… and wait… and wait…”

Suddenly, news arrives in Casablanca. Two German couriers carrying important official documents have been murdered on a train from Iran. The murderers and their possible accomplices were last seen headed for Casablanca. In response, the local French Vichy police storm into the marketplace and begin rounding up suspicious-looking people –one man is gunned down in the street for possessing expired papers. He is shot directly beneath a sign featuring Marshall Petain, head of the regional Vichy government, and a message which reads: “JE TIENS MES PROMESSES MEME CELLES DES AUTRES” (or “I keep my promises, just as I keep those of others”), reminding us of the false promises of the Vichy government.

Casablanca uses the geographic location of unoccupied French North Africa as a fascinating, shadowy, noir-esque middle-ground, or borderland, which is under the thumb of the domineering Nazi and French Vichy government. A crowded bazaar shows us a busy marketplace (the elaborate set was cleverly re-used from an earlier Warner Brothers picture, such as The Desert Song) while overhead a Nazi plane lands at the airport (the airport sequences were filmed at Van Nyus airport in Los Angeles). Despite ostensibly being a politically neutral city, Casablanca is under a curfew, and a spotlight swirls around the city, reminding us of the Nazis far-reaching gaze. Throughout the city, scores of innocent refugees are desperate to flee westward. The transitory nature of the city of Casablanca represents a multi-cultural gathering place of people filled with fear and secrets while hollow opportunists and pick-pockets lurk throughout the market, vultures who prey on travelers who “hear very little and understand even less.” Everyone seems stuck, hoping for a way out, but caught in the middle is one American man expatriate named Rick Blaine.

Who is Richard “Rick” Blaine? Sardonically played by the great Humphrey Bogart, the story of Rick is the story of America –wounded by war, Rick is wary of foreign entanglements but throughout the film he is transformed from a self-professed isolationist into a defender of the downtrodden, even a “patriot.” Deep down, he has always been a “sentimentalist” while presenting himself in a “cynical shell.” He is a man caught between extremes –neither hero nor a villain– yet he has the power to choose his exit from the shadows (utterly impeccable lighting plays a key role in the film. Knowing that Nazi eyes and ears are everywhere in Casablanca, Rick claims, “I’m not interested in politics, the problems of the world aren’t in my department. I’m a saloon keeper,” and “I stick my neck out for nobody,” and “I’m not fighting for anything anymore except myself. I’m the only cause I’m interested in.” Rick is considered a “difficult customer” because one “never knows what Rick will do or why.” He is a tough, no-nonsense guy with a gruff demeanor. At one point, he laconically remarks that his nationality is as a “drunkard” and his past is kept deliberately murky. We learn that Rick was born in New York, he is thirty-seven years old, and as a young idealist, he once fought alongside the “underdog” as a fighter on the Loyalist side against the fascist Franco regime in the Spanish Civil War, and he ran guns to Ethiopia in its war against fascist Italy. Rick is, by all accounts, a left-leaning “good guy” who has taken a courageous stand against fascism (“I bet they’re asleep in New York. I bet they’re asleep all over America” he remorsefully speculates). In fact, Rick was once something of a hero in the underground movement against fascism, however, a mysterious tragedy befell him while he fled the Nazi invasion of Paris, and he wound up living under the pretense of neutrality, jaded in Casablanca while running a classy nightclub, “Rick’s Café Americain,” a place where everyone goes. Why doesn’t he return to America? Did he abscond church funds? Or run off a with senator’s wife? Or kill a man? Rick claims it’s a combination of all three. He says he came to Casablanca for his health, for the waters –but when reminded this is a desert, Rick smugly claims he was merely “misinformed” (amusingly when filming Casablanca Ingrid Bergman stood two inches taller than Bogart, so he often had to sit or stand on elevated boxes to appear taller).

We first enter Rick’s night club at eye-level as whispers and shadows pervade the scenes. Sam the black piano player (played by Dooley Wilson) sings “It Had To be You” (Wilson was actually a drummer so he pretended to play piano) –Sam is a close friend, trusted confidante, and also an employee of Rick’s. As we pan throughout the night club, we are given snippets of conversations, people plotting their escape from Casablanca –a woman tries to sell her diamond jewelry, men discuss getaway boats and trucks bustling out of the city. This is a remarkably cosmopolitan club filled with many different languages spoken by Asians, Middle Easterners, Europeans, and Americans. Apparently, some thirty-four different nationalities appear in the film, and Rick employs people of all stripes in his club –including Sam the piano player (Dooley Willson), Sascha the Russian bartender (Leonid Kinskey, Bogart’s drinking buddy), Emil the croupier (Marcel Dalio, a legendary star of French cinema who appeared in classics like Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion and La Règle du Jeu), and Carl the German headwaiter (S. Z. Sakall, typoed in the credits as “S. K. Sakall”). Sam is also occasionally joined by a cabaret singer (played by Corinne Mura). And there is also a Norwegian jewelry seller named Berger (), who is secretly a resistance fighter –“We who are still free will do what we can. We are organized monsieur, underground like everywhere else.” In the club’s private backroom, illicit gambling takes place. A Dutch banker (Torben Meyer) who runs “the second largest banking house in Amsterdam” sits at a gambling table and asks Carl the waiter if Rick will join him for a drink, but Rick maintains a policy of not drinking with customers –even to Dutch bankers who offer money for a drink with Rick. Unlike most people in Casablanca, Rick cannot be easily bribed or compelled.

We first meet Rick as he signs a check for 1,000 Francs, beside an empty martini glass, smoking a cigarette, playing a game of chess by himself (it was Bogart’s idea to include the chessboard). He confronts a German banker from Deutsche Bank (Gregory Gaye) and kicks him out of the backroom, even though the man claims to have been in every gambling room “between Honolulu and Berlin.” As he storms off, the banker threatens to report Rick to Der Angriff (a Nazi newspaper whose title means “The Attack”). Is Rick prejudiced against bankers? Surely not, because Dutch banker who runs “the second largest banking house in Amsterdam” is allowed to gamble. Even from the outset, we are given clues that Rick still maintains a staunchly anti-Nazi attitude. After all, he has been doing it all his life. Later, he rips up a German check at the bar –the moment is so subtle you might miss it. He dismisses his sometimes-girlfriend named Yvonne (Madeleine Lebeau) because she had too much to drink –Rick asks his bartender to take her home and come straight back, whereas other men might have taken advantage of her. Rick has a quiet nobility to him in these early scenes.

We also meet another nightclub owner named Signor Ferrari (Sydney Greenstreet), a large, jovial man wearing a fez who reportedly has a “monopoly on the black market in Casablanca” –here, we are asked to contrast Rick and Ferrari. While Ferrari has made his own business deals, Rick tries to remove himself entirely (“My dear Rick when will you realize that in this world today, isolationism is no longer a practical policy,” says Ferrari). A lesser club, Ferrari runs the Blue Parrot, a loose establishment more akin to an open-air bazaar than a bar, and he routinely offers to buy Rick’s Café –but Rick refuses. When Ferrari offers to buy Sam instead, Rick curtly responds, “I don’t buy or sell human beings.” In spite of his disillusionment, Rick still stands for the greatest of American values. A final point about Ferrari, he has apparently established a very lucrative business for himself with the captain of the Vichy police in which he collects hefty sums of francs in exchange for delivering attractive young women who are seeking their visas.

One of the significant recurring sub-plots in the film concerns a pair of Bulgarian newlyweds –Jan and Annina Brandel (Helmut Dantine and Joy Page) who are fleeing Bulgaria (“where the devil has the people by the throat”)in the hopes of finding safety and freedom in America. They have been married for a mere eight weeks but don’t have enough money to pay Ferrari for visas, and Annina wrestles with the prospect of sleeping with Renault in exchange for visas (all the discussion of sex in the film is handled with the utmost care in order to avoid the ire of the censorious Hay’s Code). The Brandels try to win enough money for their escape at Rick’s gambling tables, and in taking sympathy on this young couple, Rick helps them cheat by quietly instructing Jan to bet all his money #22 at the table in the backroom.

The captain of the police is Captain Louis Renault (Claude Rains), an amusing French prefect who claims to be politically neutral, he bends with the prevailing winds wherever they may lead. In this case, in spite of believing himself to be “master of his own fate,” Renault is ruled by the Nazis (“Captain, are you entirely sure which side you are on?”). He is frequently flanked by his aide, Lt. Casselle (George Dee), and Captain Tonelli (Charles La Torre) of the Italian service, both of whom are often seen squabbling with one another. He is a known womanizer who trades visas in exchange for liaisons with young women –he envies how women are attracted to Rick– yet he still respects Rick and is even friendly with him. Renault strikes us as an a-moral character at first, however he also has a very subtle disgust for the Germans, particularly for the Major Heinrich Strasser (Conrad Veidt), who arrives in Casablanca because a top target of the Nazis is set to arrive –a well-known Czechoslovakian Resistance leader and freedom fighter named Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid), who has escaped the clutches of the Nazis no less than three times across Europe, including after serving one year in a German concentration camp. He and his wife are set to arrive imminently in Casablanca. Everyone knows Victor Laszlo will be desperately searching for a way out of Casablanca, but Major Strasser plans to keep him trapped ad infinitum. Rick and captain Renault make a wager of 10,000 francs over whether or not Victor and his wife will make it out of Morocco. How could they escape? The central MacGuffin of the film concerns those two stolen irrevocable letters of transit, and as it turns out, one of Rick’s acquaintances, Signor Guillermo Ugarte (Peter Lorre) –an Italian black-market dealer in North Africa– has these transit papers in his possession. They are signed by either General Charles DeGaulle or General Maxime Weygand (the pronunciation in the film is muffled), the latter of whom was the military-Vichy commander in French North Africa. Either way, Ugarte plans to sell these papers for a fortune before escaping westward himself, but for now he gives them to Rick –unlike other people in Morocco, Rick is trustworthy and respected. Notably, Rick hides the stolen papers inside Sam’s piano (while Sam appropriately plays the song “Who’s Got Trouble? – Knock on Wood”) and soon Ugarte is arrested and killed.

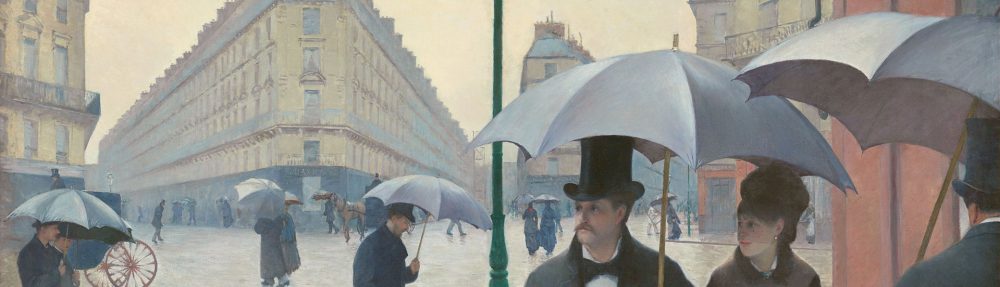

However, the story takes a turn when the Czech resistance leader Victor Laszlo arrives at Rick’s club later that evening with his wife on his arm –she is one of the most beautiful women ever to set foot in Casablanca—named Ilsa Lund (played by the radiant Ingrid Bergman whose face is captured by cinematographer Arthur Edeson in soft, veiled, almost saintly photography throughout the film). As it turns out, she is a mysterious woman from Rick’s past, and the catalyst for all of his tortured, alcoholic romanticism (“Of all the gin joints of all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine”). In a flashback from some time ago, Rick and Ilsa met in Paris and quickly fell in love. Rick was a left-leaning revolutionary of sorts (on the Nazi blacklist) and Ilsa both loves and admires him for it. At the time, they had a rule of “no questions” but Ilsa once admitted there was another man in her life but that now “he’s dead.” As Ilsa and Rick drift through Paris –sailing on the Seine, smiling by the Eiffel Tower, and listening to their friend Sam play a heartachingly beautiful song entitled “As Time Goes By” — Rick frequently toasts to Ilsa (“Here’s looking at you, kid”).The last time they met was La Belle Aurore the day the Germans marched into Paris (Rick remembers every detail –the Germans wore grey, while she wore blue). But when they try to escape, Rick is left standing alone in the rain at the train station, with a note in his hand from Ilsa claiming she cannot go with him. Distraught, Rick leaves Paris on the train to Marseilles. Now in Morocco, Rick blames Ilsa for breaking his heart. He angrily refuses to give Victor and Ilsa the transit papers until Ilsa reveals the truth –she and Victor were married (though they kept their marriage a secret even from close friends) but one day Victor was arrested and placed in a Nazi concentration camp. For months, Ilsa frantically tried to receive word of his whereabouts until the sad news reached her that while Victor was trying to escape, he was killed. In her loneliness, she and Rick struck up a wonderful romance. However, around the time that the Nazis invaded France, Ilsa discovered that Victor had survived and while he was sickly, he needed tending. This is why Ilsa abandoned Rick.

Meanwhile inside Rick’s club, confrontations between the Germans and everyone else reach a boiling point, culminating in the famous scene of the “dueling anthems.” It begins with a roudy cohort of Germans singing the Nazi anthem Die Wacht am Rhein (“The Watch on the Rhine”) which is quickly overwhelmed and drowned out by a rousingly patriotic rendition of La Marseillaise led by Victor Laszlo (with subtle approval by Rick). It is an incredibly moving, inspirational moment, which apparently brought tears to the eyes of the cast and crew on set, many of whom had actually fled from the Nazis themselves. This patriotic musical number earns the ire of the Nazis –Major Strasser instructs Captain Renault to find an excuse to close down Rick’s club, at which point Renault comically remarks he’s “shocked, shocked to find gambling is going on in here” while also collecting his personal winnings. Despite having to close on a tight budget, Rick promises to keep his whole staff salaried.

Shortly thereafter, Rick comes to his senses and devises a plot to help Victor and Ilsa escape from Casablanca. He sells his club to Ferrari and persuades Captain Renault that he will help him ensnare Victor Laszlo (thereby letting him win the 10,000-franc bet), but Rick ultimately betrays Renault and leads Victor and Ilsa out to the airport, convincing Ilsa she must depart with her husband (“If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today, and maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life”). Rick claims he has a job to do and that he and Ilsa will “always have Paris.” He tragically lets her go, and when Major Strasser arrives on the scene, Rick shoots him dead. He has finally come full circle in the film. As the police close-in, Renault decides not to arrest Rick and instead to “round up the usual suspects.” He then pours himself a drink, but upon noticing that it is Vichy water, he disgustedly tosses it into the trash and kicks it over. With both men facing trouble, Rick and Renault discuss plans to travel together to the free French garrison at Brazzaville (using the 10,000 francs Rick has evidently won from Renault). The film closes with a new beginning as Max Steiner’s triumphant motif of La Marseillaise plays and Rick remarks:

“Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

After rediscovering his love for Ilsa, and also reawakening his commitment to an ideal, Rick realizes that he can neither forget nor hide from his past. Rick’s struggle between right and wrong in Casablanca is best reflected in the film’s carefully constructed mise-en-scène, a playful intermittent use of light and shadows, mixing together noir and expressionist tropes. Darkness throughout the film is contrasted with high-contrast low-light, as the darkness of night is regularly interrupted by a spotlight over the city, and Rick’s striking white suit stands out among a crowd of haziness, but as he visually descends further into darkness, so too does the lighting on his face. Indeed, the very title of the film points us toward a patriotic celebration of the “white house” (or the “casa blanca”) as those characters who move toward the light are increasingly reaching out for hope and freedom. Another chief motif in Casablanca includes the various kinds of alcohol consumed by different characters. A careful study of who drinks what –such as champagne, brandy, wine, whiskey, or bourbon– will illuminate a great deal about this immensely textured film. For example, one moment that sticks out to me in particular concerns a brief moment wherein Major Strasser (a German) attempts to order champagne but Captain Renault (a Frenchman) insists that he drink nice bottle of French wine (Veuve Cliquot ’26) while eating Russian caviar. While on the surface, this subtle –almost forgettable—moment could be easily passed over, I think it shows to us Renault’s nationalistic pride, as well as his quiet repressed bitterness toward the Germans. After all, only moments later Renault sits down to drink champagne with Victor Laszlo and Ilsa Lund. It foreshadows his own decision to reject neutrality and fight back. It also echoes his other passive-aggressive jabs at Major Strasser when he insults the “blundering” Americans, but Captain Renault responds with, “We mustn’t underestimate American blundering. I was with them when they blundered into Berlin in 1918.” Rick is not the only character in Casablanca who loses his disillusionment and discovers an inner sense of heroism.

A blend of noir, expressionism, and melodrama, as Umberto remarks in in The Clichés Are Having a Ball, in Casablanca: “Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred cliches move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion.” While it was never really intended to be a classic back in 1942, nevertheless a perfect combination of talents has yielded a panoply of reimagined Hollywood clichés presented in a ceaselessly satisfying new way –featuring the talents of director Michael Curtiz, screenwriters Howard Koch and the Epstein Brothers (Julius and Philip), cinematographer Arthur Edeson, editor Owen Marks, composer Max Steiner, and producer Hal Wallis (under Jack Warner of Warner Brothers). In keeping with the themes of the film, Casablanca was an optimistic cosmopolitan endeavor both on and off-screen –a hopeful vision of the best of American virtues.

Click here to return to my film reviews.

- Director: Michael Curtiz

- Screenplay by: Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, and Howard Koch

- Based on: “Everybody Comes to Rick’s” by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison

- Produced by: Hal B. Wallis

- Starring:

- Humphrey Bogart…..Rick Blaine

- Ingrid Bergman…..Ilsa Lund

- Paul Henreid…..Victor Laszlo

- Claude Rains…..Captain Louis Renault

- Conrad Veidt…..Major Heinrich Strasser (Veidt was a refugee German actor who had fled the Nazis with his Jewish wife, but frequently played Nazis in American films. He was the highest paid member of the cast in Casablanca despite his second billing).

- Sydney Greenstreet…..Signor Ferrari

- Peter Lorre…..Signor Ugarte

- Curt Bois…..a pickpocket (Bois had one of the longest careers in cinema, spanning over 80 years).

- Leonid Kinskey…..Sascha, the Russian bartender who is infatuated with Yvonne (Kinskey told Aljean Harmetz, author of Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of Casablanca, that he was cast because he was Bogart’s drinking buddy. He was not the first choice for the role; he replaced Leo Mostovoy, who was deemed not funny enough).

- Madeleine Lebeau…..Yvonne, Rick’s soon-to-be-discarded girlfriend (Lebeau was a French refugee who had left Nazi-occupied Europe with her husband Marcel Dalio, who was a fellow Casablanca performer. She was the last surviving cast member until her death on May 1, 2016).

- Joy Page…..Annina Brandel, the young Bulgarian refugee (Page was the step-daughter of studio head Jack L. Warner).

- John Qualen…..Berger, Laszlo’s Resistance contact.

- S. Z. Sakall…..Carl, the waiter (credited as S. K. Sakall)

- Dooley Wilson…..Sam (Wilson was one of the few American-born members of the cast. A drummer, he had to fake playing the piano. Even after shooting had been completed, producer Wallis considered dubbing over Wilson’s voice for the songs).

- Uncredited Roles:

- Marcel Dalio…..Emil the croupier (Dalio had been a star in French cinema, appearing in Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion and La Règle du Jeu).

- Helmut Dantine…..Jan Brandel, the Bulgarian roulette player married to Annina Brandel.

- Gregory Gaye…..the German banker who is refused entry to the casino by Rick.

- Torben Meyer…..the Dutch banker who runs “the second largest banking house in Amsterdam.”

- Corinna Mura…..the guitar player who sings “Tango Delle Rose” (or “Tango de la Rosa”) and later accompanies the crowd on “La Marseillaise.”

- Frank Puglia…..a Moroccan rug merchant

- Richard Ryen…..Colonel Heinze, Strasser’s aide

- Dan Seymour…..Abdul the doorman

- Gerald Oliver Smith…..the Englishman whose wallet is stolen

- Norma Varden…..the Englishwoman whose husband has his wallet stolen

- Cinematography: Arthur Edeson

- Edited by: Owen Marks

- Music by: Max Steiner

- Production Company: Warner Bros. Pictures

- Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures

You bought me when you mentioned that it was considered as one of the great propaganda films for the Allies in the war. In my opinion, surely it was. Magnificent power, it must have had.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It gave me the best respect for Bogart’s iconic delivery of film quotes with “We’ll always have Paris.” and “Here’s looking at you, kid.”

LikeLiked by 1 person