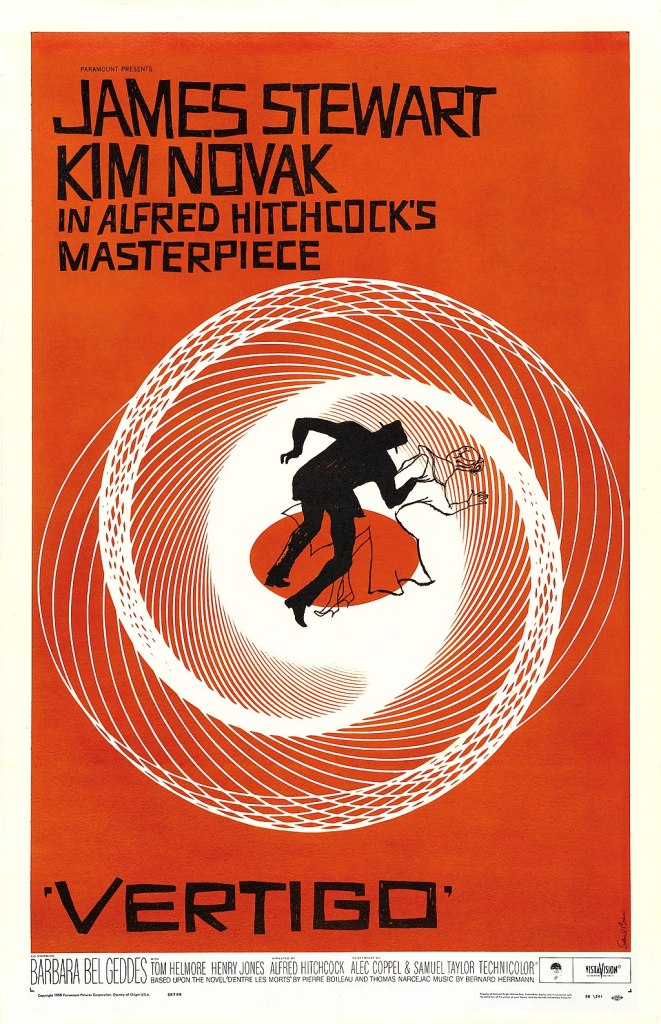

Vertigo (1958) Director: Alfred Hitchcock

“Do you believe that someone out of the past, someone dead, can enter and take possession of a living being?”

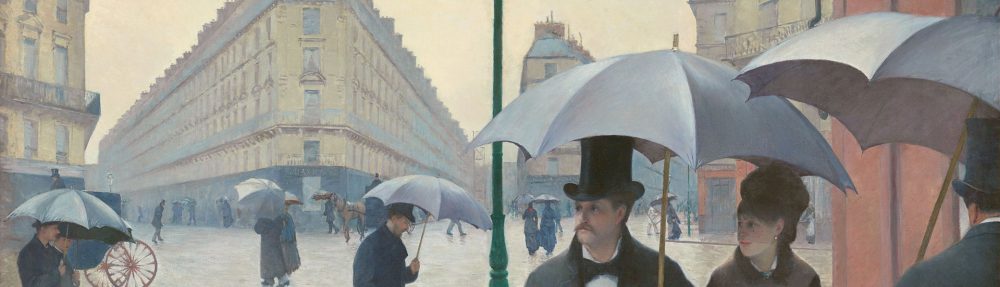

I recently had the rare opportunity to see Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo on the big screen with my Dad in what proved to be an utterly overwhelming, moving, transcendent experience. This stunning gem of a film remains Hitchcock’s masterpiece for good reason. As recently as 2012, it unseated Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane in a critics’ poll of the greatest films ever made by Sight & Sound magazine, and then it came in 2nd in another survey in 2022. Vertigo is a towering giant of a film today, although upon initial release it was not as highly praised. The idea for Vertigo was inspired by the books of French writers Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. After reading one of their books, Celle qui n’était plus (“She Who Was No More”) which was made into Henri-Georges Clouzot’s film entitled Les Diaboliques, Hitchcock encouraged Paramount to acquire the rights to the next book, D’entre les morts (From Among the Dead) by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Against the wishes of producer Herbert Coleman, Hitchcock initially approached playwright Maxwell Anderson in 1956 to create a first-draft screenplay of the novel, however after Anderson submitted his screenplay —Darkling, I Listen— Hitchcock was so disappointed with it that he instructed the Coleman to “burn it.” He then turned to his friend Angus MacPhail who was struggling with chrnic alcohol addiction and was unable to complete the script (this was his last script before he passed away in 1962), and Hitchcock then turned to Alec Coppel who is rumored to have previously worked on To Catch A Thief in an uncredited writing role. After Coppel, Hitchcock used Maxwell Anderson and also Samuel Taylor, who apparently had an in-depth knowledge of San Francisco. With so many writers working on the script, the Writer’s Guild was asked to weigh in and they concluded that credit should be given to Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor. During the build-up to the production of Vertigo, Hitchcock was hospitalized following dueling procedures to cure a navel hernia, colitis, and gallstones. During recovery, Hitchcock contemplated his own death and the result was his desire to make a movie about his personal fears, obsessions, and his desire to reanimate the ghostly past.

In an unsettling opening credits sequence designed by frequent Hitchcock collaborator Saul Bass (in his first collaboration with Hitchcock before designing credit sequences in Psycho and North by Northwest). The film’s opening visuals are coupled with Bernard Herrmann’s haunting, unforgettable score (inspired by Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde) with an extreme close-up of Kim Novak’s eye and lips before we are transported to the rooftops of San Francisco where two cops are chasing a fugitive (from the right side of the screen to left) as he hops from roof to roof. John “Scottie” Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart) makes the leap and dangles dangerously from a rain gutter as he fearfully looks down at the ground below –his perspective becomes warped, dizzy, and twisted in the first use of the famous “vertigo effect” or the “dolly zoom effect.” The other unnamed police officer attempts to help Scottie, but he slips and falls to his death. This is the first of several tragic downfalls in the film, though notably Scottie hangs on, refusing to fall. He will arguably remain in this dangling state for much of the rest of the film. And this is also the first moment that Scottie learns he suffers from acrophobia, or vertigo, as he develops a sense of guilt and shame at his condition. As with other Hitchcock protagonists, like L.B. “Jeff” Jeffries in Rear Window (also played by Jimmy Stewart), Scottie is a flawed, weakened, and even slightly emasculated figure. In the next scene, for example, we see him with a cane, wearing an uncomfortable corset while recuperating from his episode. How did he ever manage to get down off the roof? It is never explained, though Scottie has clearly sustained an injury.

The next scene takes us into the apartment of Marjorie “Midge” Wood (Barbara Bel Geddes), a friend and former paramour of Scottie. She is an artist working on an advertisement of new brassier based on the design of the cantilever bridge. Notably, a cantilever bridge is constructed based on the principle of balance, with weight being shifted via torque and rotational equilibrium. Similar, throughout Vertigo, Scottie is seeking balance after having his viewpoint obstructed and disoriented. At any rate, Scottie is a sympathetic figure in these early sequences –he is wounded, slightly silly, crippled with fear, and even faints in Midge’s arms, unable to stand on a simply step-stool. He has been forced to abandon his dream of becoming captain of the police force due to his vertigo. He fears that his acrophobia could cause someone else to die. In spite of his weaknesses, Midge seems to be privately infatuated with him. At one point, they were engaged for three weeks many years ago. Strangely they attended college together, even though Scottie appears to be about 20 years her senior. Midge serves as a kind of reliable caregiver for Scottie –indeed even a maternal figure for him. Their relationship is unusual as Scottie never seems to knock on her door, he just enters her apartment freely. There is a notable absence of romance between the two of them. We in the audience desire for them to rekindle their romance, but there is minimal sexual tension between them. Instead, their world feels ordinary and modern, lacking in excitement. Despite being scarred physically and psychologically, men like Scottie secretly desire an impassioned romance, not an Oedipal motherly nurse for a lover. He complains that his corset binding is tight and constricting, and that he wants to be a “free man,” hoping to ironically toss his cane out the window. He wonders if he can ever be rid of his acrophobia and regain what he has lost but Midge claims he simply belongs behind a desk. Already, Scottie is unable to let go of the past. She plays a bit of Mozart music but it frustrates Scottie, and she suggests the only way he might be rid of his acrophobia is death:

“…only another emotional shock would do it, and probably wouldn’t. You’re not gonna go diving off another rooftop to find out!”

In the next scene, Scottie is summoned to the office of an old college acquaintance and current ship-building magnate, Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore). It is located on the Embarcadero in the Mission District. Mr. Elster is a sharp-dressed in a large, ornate private office adorned with chandeliers, mahogany furniture, and 19th century artwork of old San Francisco. The contrast between the two men is stark. Elster shares that he has married into the “dull” business of shipbuilding, but his wife’s family have now all died. He pines for the vanished world of old San Francisco, a place he imagines in his paintings:

“The things that spell San Francisco to me are disappearing fast… I should have liked to have lived here then – color, excitement, power, freedom.”

Elster briefly mentions how sad he was to read about Scottie’s accident and his subsequent vertigo diagnosis, before revealing his true purpose for contacting Scottie. Elster is concerned about his wife and wants to hire Scottie for a “special favor” to follow her around –he fears she is threatened from “someone dead.” She often enters a trance-like state and seems to lose herself entirely, wandering around during the day, forgetting where she has been, as if she has been possessed by someone else. She apparently has gone to sit by the water in Golden Gate Park, gazing out at the pillars, or “portals of the past.”

Do you believe that someone out of the past, someone dead, can enter and take possession of a living being?

A skeptical Scottie scoffs at the idea of a ghostly possession can take ahold of a person, but he still agrees to see what Elster’s wife looks like that evening at Ernie’s restaurant. That night, while seated at the bar in the lavish, aristocratic, ruby-red walled Ernie’s, Scottie looks upon Madeline for the first time (played by Kim Novak). Her striking appearance immediately gives audiences (and also Scottie) a sense of grace, elegance, and beauty. Scottie watches her half-profile as the bright red walls seem to pulse with intoxication. This is the start of Scottie seemingly “falling” in love.

The following day, Scottie follows a gray-suited Madeleine around San Francisco as she drives (mostly downhill, and then left-to-right, left-to-right). He shadows her from her apartment in the famous Brocklebank Apartments, to a backalley entrance to a colorful florist (the scene of Scottie stalking Madeleine from a crack in the door in the shadows as the door opens to reveal a world of exuberance is somewhat reminiscent of The Wizard of Oz). Scottie then tails Madeleine to the Legion of Honor where she sits and admires a painting of a woman named Carlotta Valdes, and the cemetery at Mission Dolores (Mission San Francisco de Asis), where she gazes down at a gravestone for Carlotta Valdes, a woman born on December 3, 183 and died on March 5, 1857 (at the age of 26). Lastly, he also tails Madeleine to the McKitrick Hotel to an upper room, though the hotel manager (played by Ellen Corby) claims that a woman named “Carlota Valdes” does indeed rent the upper room but she has not been in today.

From here, Scottie loses Madeleine and he returns to Midge’s flat where they talk about finding a San Francisco historian who knows about the “gay old Bohemian days of gay old San Francisco –juicy stories like who shot who in the Embarcadero in August 1879.” Midge leads Scottie to the Argosy Book Shop where they speak with Pop Liebel (Konstantin Shayne), a European man who runs the high-end bookshop. However, Liebel speaks with a foreign accent, perhaps German, which suggests his knowledge of San Francisco history has been learned rather than inherited. He explains that Carlotta Valdes came from somewhere small, a mission settlement south of the city (later we learn this place is San Juan Bautista), and she was found by an unnamed wealthy, powerful man as she was dancing and singing cabaret. And he built for Carlotta the great mansion in the Western Addition (the McKitrick Hotel), but after they had a child out of wedlock together, the unnamed man simply disposed of Carlotta, such that she became the “sad Carlotta” and eventually the “mad Carlotta” before ultimately committing suicide. Apparently, “there are many such stories.” Curiously, like Gavin Elster, Pop Liebel also romanticizes wistfully about the halcyon bygone days of old San Francisco, an era where “a man could do that in those days. They had the power and the freedom.” Even a cruel man tossing his mistress aside such that she committed suicide is still a reason for nostalgic yearning among the men of Vertigo. Though they might publicly deny it, what they secretly desire is power and freedom.

Gradually, the lights in the bookshop are dimmed (almost to the point that we did not notice) and as Midge and Scottie leave, Pop Liebel brightens up his shop again. Midge pledges to view the Carlotta Valdes portrait, while Scottie speaks with Gavin Elster again, this time at his elite gentleman’s club. Here, Elster shares that Madeleine’s obsession with Carlotta Valdes makes no sense since she does not know anything about her great-grandmother who went mad and killed herself. Yet now she wears the family jewelry she has unwittingly inherited from Carlotta. Scottie takes a stiff drink as he starts to question if Madeleine might actually be possessed with the spirit of Carlotta Valdes.

“Well, I think that explains it. Anyone could become obsessed with the past with a background like that!”

The next day, Scottie follows Madeleine again through her typical routs, only this time she drives down along Presidio Drive and Fort Pointe to just beneath the Golden Gate Bridge as she slowly tosses her flowers into the bay, one by one, and then she herself leaps into the frigid waters. At this point, Scottie decides he can no longer play the role of passive observer (or perhaps silent voyeur) and he jumps into the bay to rescue her.

Later, she awakens inside his lone apartment, startled and nude in Scottie’s bed while her clothes are drying in the kitchen. Interestingly enough, Scottie has stripped Madeleine of all her clothes offscreen in an abrupt rupture with his former position as a silent observer. However, defying all expectations, Madeleine is not terrified after having awoken naked in a strange man’s bed. Instead, she is excited by the situation, even seductive, elusive, enigmatic, and confidently flirtatious with Scottie, praising his name John Ferguson for being “a good strong name.” Old friends call him John, acquaintances call him Scottie.

There is a brief moment in the evening of Midge driving past Scottie’s house in a fit of jealousy as Madeleine (a “ghost”) leaving his house, and the next day, Scottie follows Madeleine in her green car as they proceed primarily downward, descending (not ascending) the hills in San Francisco. He catches her dropping a letter at his apartment and they decide to escape and wander together as they head to the Muir Redwoods where the encounter the “oldest living things,” the Sequoia sempervirens, which are “always green, ever-living.” These 2,000-year-old trees are yet another link with the past. The spiraling, cyclical rings on a felled tree trunk shows just how far back their history leads, nearly a thousand years to the Battle of Hastings and beyond. The redwood trees are symbolic reminders of the lingering presence of the past.

After Madeleine confesses a nightmare in which she walks into a dark corridor in an old Spanish mission, Scottie takes her “somewhere in the light” by the Monterey shoreline beside Monterey cypress trees, which can also live for thousands of years. The agedness of the trees serves as the backdrop to the budding romance of Scottie and Madeleine –he pledges himself as “committed” and “responsible” because according to “the Chinese… once you’ve saved a person’s life, you’re responsible for it forever.” They embrace and kiss for the first time in a stunning scene of crashing ocean waves and an explosive crescendo of Bernard Herrmann’s score.

Meanwhile, Midge has apparently had a “desperate urge” to see Scottie, but when he shows up at her flat, Midge has coyly painted an amusing portrait of herself as Carlotta Valdes –a parody of the painting on display in the Legion of Honor. However, Scottie doesn’t find her painting funny and he abruptly departs, leaving a frustrated Midge alone in her apartment where she ruins her painting.

The next morning, Madeleine suddenly arrives at Scottie’s doorstep (her face is silhouetted) and she claims to have experienced the same recurring dream about a Spanish mission. As she describes the place, Scottie puts the pieces of the puzzle together and realizes she is referring to San Juan Bautista, a little mission town about 100 miles south of San Francisco which has been historically preserved –it marks yet another thematic link with the past. Now no longer suggesting Madeleine should visit a mere psychiatrist, he offers to drive her to San Juan Bautista and purge her of this dark vision. Scottie has now completely transformed from voyeur to hero, believing he can save Madeleine.

Later, as they sit in a carriage in the stable at San Juan Bautista, Madeleine reflects on the town: “There were not so many carriages then. There were horses in the stalls: a bay, two black, and a gray. It was our favorite place. But we were forbidden to play here. Sister Teresa would scold us.” They kiss twice and profess their love for one another as Madeleine struggles to escape from him, saying “no, it’s too late…” and “it wasn’t supposed to happen this way. It shouldn’t have happened…” She then rushes into the church and up the bell tower while Scottie tries to run after her, but he quickly succumbs to acrophobia on the old wooden, rickety staircase. And outside the stairwell window, Scottie sees Madeleine fall to her death –an apparent suicide.

In a sobering trial scene, Elster and Scottie are exonerated and the death of Madeleine is ruled a suicide. However, the judge rebukes Scottie for causing the death thanks to his “weakness” showing him to be “powerless when he was most needed.” He failed to disrupt Madeleine’s suicidal tendencies. And after the trial, Elster reassures Scottie that everything will be alright and that he plans to escape San Francisco and move to Europe. But distraught and in disbelief, Scottie begins having terrifying nightmares of Madeleine’s dreams, and he soon experiences a psychotic break. His internal balance and equilibrium has been upturned. He is committed to a sanitarium where he is forced to listen to Mozart. Midge visits him, reassuring him that “mother’s here, Johnny,” but Scottie remains unresponsive. After speaking to the doctor and suggesting that Mozart won’t be helpful, she sadly trudges out of the facility –this is the final scene in the film featuring Midge.

In time, Scottie regains his independence, but he is not the same. He is now a broken man, hopelessly visiting all the places where he once followed Madeleine. Then one day, he spots a woman on the street bearing an uncanny resemblance to Madeleine, albeit with red hair. He follows her up to her room at the Empire Hotel where he essentially forces his way into her room and obsessively asks her questions. We learn that her name is Judy Barton from Salina, Kansas who works at Magnin’s. After considerable pressure, Judy relents and agrees to have dinner with Scottie. As he departs, the audience is confronted with a maddening, startling, lengthy close-up of Kim Novack’s face as she breaks the fourth wall and explains Elster’s plot while drafting letter she later disposes of. From this point onward, we switch allegiances. The audience begins to sympathize more with Judy rather than the increasingly, maddeningly obsessed Scottie. As it turns out, Gavin Elster devised this complicated hoax in order to murder his wife, claim her family money, and flee to Europe. He hired Judy to act as his wife, and the woman who was tossed from the bell tower in San Juan Bautista was actually Elster’s true wife –about whom we know nothing—her neck was apparently broken prior to this event. It was all a deception in order for Elster to live like the men of old San Francisco who had the “freedom” and “power” to toss their wives aside. He knew that Scottie was diagnosed with vertigo and would not have been able to make it to the top of the tower (though Hitchcock lamented to Francois Truffaut that Scottie being unable to finish climbing to the top of the bell tower, was an unfortunate plot-hole that Gavin Elster could not have possibly foreseen). But Judy confesses she did not anticipate falling in love with Scottie.

As Judy and Scottie begin to spend more time together, Scottie quickly grows maniacal and controlling. The “everyman” that we sympathized with at the start of the film has now become villainous and obsessive, perhaps even possessive. He badgers Judy until she starts dressing like Madeleine and even dies her hair platinum blonde until –in a stunning, moving sequence—Judy emerges from her hotel bathroom in a haze of green looking exactly like Madeleine in Scottie’s earful eyes. The embrace and passionately kiss in a wild, spinning, vertigo-infused passion as Bernard Herrmann triumphant score plays. As the room spins, with the green glow of the Empire Hotel sign outside the window, Scottie imagines himself back in the horse stables in San Juan Bautista with Madeleine. He has somehow accomplished the impossible –he has managed to resurrected the past, and bring the dead back to life.

However, something is not right. When Judy places a necklace around her neck, Scottie notices in the mirror that she is wearing the exact same necklace that Madeleine wore when she supposedly channeled Carlotta. And it all becomes clear to Scottie –he has been made the foolish victim of an elaborate fraud scheme. Madeleine was nothing more than a fictive character, a fantasy woman in a false narrative. Judy was only playing a role. In a fit of anger, Scottie drives Judy down to San Juan Bautista as she grows increasingly concerned and he says there’s “One final thing I have to do, and then I’ll be free of the past.” When they arrive, he forces Judy into the mission and up the old belltower, furious at her deception:

“You played the wife very well, Judy. He made you over, didn’t he? He made you over just like I made you over. Only better. Not only the clothes and the hair. But the looks and the manner and the words. And those beautiful phony trances. And you jumped into the Bay, didn’t you? I’ll bet you’re a wonderful swimmer, aren’t you? Aren’t you? Aren’t you? And then what did he do? Did he train you? Did he rehearse you? Did he tell you exactly what to do and what to say? You were a very apt pupil, too, weren’t you? You were a very apt pupil. Why did you pick on me? Why me? I was the set-up. I was the set-up, wasn’t I? I was a made-to-order witness.”

When they reach the top, Scottie realizes he has not succumbed to his vertigo. At the top of the bell tower he interrogates Judy in a rage, speculating that she was Gavin Elster’s “girl” who rehearsed the scene so well –”What happened to ya? Did he ditch ya? Oh Judy, with all of his wife’s money and all that freedom and that power and he ditched you. What a shame!”

Scottie cries that he was truly in love, calling her “Maddy” –a combination of Madeleine and Judy. And as she returns his love, they embrace but Scottie whispers “It’s too late… there’s no bringing her back.” Just then a terrifying shadowy figure emerges next to them and says, “I hear voices…” Terrified that this might be the ghost of the real wrongly murdered Madeleine, Judy takes a step back and screams as she falls to her death, following the same path as Madeleine’s body. Out of the shadows emerges a nun who makes the sign of the cross and begins ringing the mission bell as Scottie steps out onto the belfry ledge, gazing down at Judy’s lifeless body while the wind blows his tie and Bernard Herrmann’s poignant, swelling score ends on an indelible note. Did Judy purposefully leap to her death? Has Scottie been cured of his vertigo? Will he join his fictional beloved Madeleine in death by also jumping off the tower? Or will he go mad again? The film ends in a moment of ambiguity as the scene fades to black.

There was an alternative ending Hitchcock was forced to shoot to satisfy the “foreign censors” wherein Midge can be seen seated beside a radio listening to the impending arrest of Gavin Elster in Europe. Another report begins about UC Berkeley students leading a cow up the steps to a campus building when Scottie arrives and they share a drink together.

Vertigo is a film enriched by Hitchcock’s meticulous attention to detail –from the prodigious use of red and green colors, to the subtle imagery of “descending” or “downfalls” (Scottie always drives down San Francisco streets, never up)—in many respects, Scottie represents Hitchcock’s alter ego as the fanatical Pygmalion visionary who is hellbent on reawakening the past and bringing the dead to life. He is a confession of Hitchcock’s own weaknesses and indulgences as an auteur. But Madeleine is a fictional character, Scottie has fallen in love with a woman who does not exist –Hitchcock’s trademark fetishized icy blonde. He prefers the ghostly history of his dreamworld with the elegant Madeleine instead of the real world filled with ordinary working women like Judy and Midge. In the dreamworld, he is a heroic rescuer of a woman possessed by her past. In the real world, he is a physically and psychologically handicapped while being mothered by Midge. But in preferring his dreamworld to the real world, he loses both the dream and the reality as “Maddy” dies.

In presenting us with this troubling tale, Hitchcock exposes the moviegoing audience’s desire to transition from passive spectator to active participant, just as Scottie does with Madeleine after she falls into San Francisco Bay. Hitchcock reveals the fantasy of the “everyman” as Scottie desires the very same imagined “freedom” and “power” held by men in the past, as romanticized by Pop Liebel and Gavin Elster. If confronted with the same suspension of disbelief and disorientation as Scottie –or “vertigo”—every person is secretly susceptible to this same fantasy, becoming swept up in a wild heroic tale wherein they might fall in love with a married woman who hearkens back to the Spanish “Californio” age of Alta California. He is even willing to place himself squarely in a supernatural horror story. The human psyche is traumatized by a natural fear of falling, and it requires a degree of balance and equilibrium, like a cantilever bridge, though it secretly desires the safety of a movie which allows the mind to “fall” into an impossible fiction without facing the consequences.

The classic MacGuffin of Vertigo is the spirit of the dead Carlotta Valdes in Madeleine, but unlike a door-key in Notorious or coded military secrets in The Thirty-Nine Steps, Carlotta Valdes in Vertigo is a mere apparition. She is intangible and therefore Scottie must discover a way to possess Madeleine in order to fully purge her of the past. But what does it actually mean to be haunted by the past? To what extent is Scotty, himself, also haunted by the past –the very same kind of possession he refuses to accept as true at the start of the film? In what ways is he also unable to let go?

Vertigo is a fever dream of all things disturbing, alluring, and terrifying. It offers a warped hero’s journey saturated with a sense of realism. It is a ghost story that simultaneously reminds us of the painful absence of ghosts and those who have died –and yet we still desire to believe in phantasms. We still believe that we know fictional characters, like people who have long since died. Like Scottie, we refuse to accept death. So the audience wants to be shocked –like tourists on a journey through sexual pathology and quixotic fantasy– and to have our disbelief suspended, as if expecting to be in a state of confusion and vertigo. Amidst repetitive imagery of circles, such as eyeballs and Madeleine’s spiral haircut which is made to perfectly match the spiral in Carlotta Valdes’s hair, Hitchcock also presents a masterclass in cinematic framing in Vertigo, showing us what happens when Scottie almost exclusively desires to move from the right side of the screen to the left, searching for balance while also desperate to relive his fantasy.

Amazingly, despite being such a stunning, powerful, evocative film –with cinematography that positively shimmers and radiates in each scene– Vertigo was initially met with mixed reviews and it was critically considered one of Hitchcock’s lesser movies. Thankfully, in the ensuing decades Vertigo has undergone a critical reappraisal and it was masterfully restored in the 1980s to great fanfare.

Click here to return to my film reviews.

Click here to return to my reviews of Alfred Hitchcock’s filmography.

Credits:

- Director: Alfred Hitchcock

- Screenplay by: Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor

- Based on: D’entre les morts, a 1954 novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac

- Produced by: Alfred Hitchcock

- Starring:

- James “Jimmy” Stewart…..John “Scottie” Ferguson

- Kim Novak…..Judy Barton/Madeleine Elster

- Tom Helmore…..Gavin Elster

- Barbara Bel Geddes…..Marjorie “Midge” Wood

- Henry Jones…..the coroner

- Raymond Bailey…..Scottie’s doctor

- Ellen Corby…..manager of the McKittrick Hotel

- Konstantin Shayne…..Pop Liebel (Argosy bookstore owner)

- Lee Patrick…..car owner who is mistaken for Madeleine

- Cinematography: Robert Burks

- Edited by: George Tomasini

- Music by: Bernard Herrmann

- Production Company: Alfred J. Hitchcock Productions

- Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Other Notes:

- Hitchcock Cameo: Elster’s Mission District shipyard company (notably Hitchcock moves from the left to right of the frame, in contrast to the direction Scottie tends to move throughout the film).

- Vera Miles was under contract with Hitchcock and was all set to star in the film but she became pregnant.

- The famous “dolly zoom effect” or the “vertigo effect” was inspired at a party wherein Hitchcock was inebriated and noticed that while his perspective could focus on a particular point, the world around it became warped and disorienting. It was initially conceived during the making of Hitchcock’s Rebecca, but was employed by Paramount second-unit cameraman Irmin Roberts in which he gradually zoomed in the camera on a focal point while simultaneously physically tracking the camera backward. The effect was used in many other classics like Jaws and Lord of the Rings.

- The initials for “Scottie” Ferguson are SF, a nod to San Francisco.

- Edith Head was the famous costume designer in Vertigo.

- Vertigo was shot in VistaVision, a technology developed by Paramount Pictures to give films a grander scope to combat the rise of home television.

- Scottie’s surrealist nightmare sequence was designed by John Ferren, a contemporary of Parisian artists like Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Henry Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. He also created the painting of Carlotta Valdes.

Vertigo Locations:

- Ernie’s restaurant was initially a humble establishment founded at the turn of the 20th century by Ernie Carlesso as an Italian and French restaurant At the time it was called Ernie’s Il Travatore. Located at 847 Montgomery Street near Jackson Square, it was on the edge of the Barbary Coast, a red-light district that had been known throughout the world since the 1850s for its brothels, saloons, opium dens, gambling and dance halls, and restaurants with discreet private dining rooms upstairs where additional services could be provided. Sadly, Ernie’s permanently closed in 1995. While the interior and exterior shots of Ernie’s in the film were sets, the real restaurant was actually used in Woody Allen’s Take the Money and Run. Location: 847 Montgomery Street.

- Brocklebank Apartments (1000 Mason Street), where the Elsters live is located in Nob Hill on the corner of Mason and Sacramento.

- The McKittrick Hotel was a privately owned a Victorian mansion from the 1880s at Gough and Eddy Streets, it was torn down in 1959 and is now an athletic practice field for Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory School.

- The Podesta Baldocchi florist shop was located at 224 Grant Avenue. The Podesta Baldocchi flower shop now does business from a location at 410 Harriet Street.

- Scottie’s apartment is located at 900 Lombard St., about one block down the hill from the notorious zig-zag block.

- The Empire Hotel was called the York Hotel but has since been renamed the Hotel Vertigo. It is located at 940 Sutter St., San Francisco, CA.

- The Palace of Fine Arts is briefly featured as is Coit Tower which Hitchcock stated was included as a phallic symbol.

- The sanitorium that Scottie visits was St. Joseph’s Hospital across from Buena Vista Park, but it was closed in 1979 and then converted into condominiums.

- The Argosy Bookstore, owned by Pop Liebel, was not real and was instead created on a Paramount lot. But it was based on the Argonaut Book Store, which still exists near Sutter and Jones

- The Muir Woods National Monument is actually Big Basin Redwoods State Park. However, the slice of a redwood tree is a copy of one that is still currently on display in Muir Woods National Monument.

- The coastal Monterey area where Scottie and Madeleine first kiss is located at Cypress Point on 17 Mile Drive near Pebble Beach, although the lone tree featured in the film was actually a prop.

- Today, San Juan Bautista looks much the same it did when Hitchcock shot Vertigo. The one famous addition Hitchcock added for the film is the giant bell tower. Apparetly, Hitchcock initially visited San Juan Bautista before the bell tower was torn down due to dry rot, and he was disappointed to learn the tower was no longer standing when he began to shoot Vertigo.