“Irrational streams of blood are staining earth…”

-Yeats

“O yonge Hugh of Lyncoln –slayn also

With cursed Jewes, as it is notable, for it is but a litel while ago–

Preye eek for us, we synful folk unstable,

…”

-Chaucer

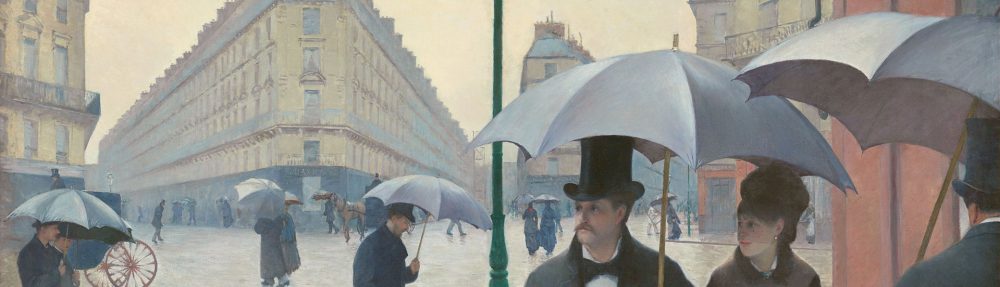

Winner of both the Pulitzer Prize as well as the National Book Award in 1967, Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer is dedicated to Malamud’s son Paul. It tells the agonizing, harrowing tale of Yakov Shepsovitch Bok, a poor Ukrainian Jew and skilled tradesman (or “fixer”) whose barren wife, Raisl, has abandoned him. Her father, Shmuel, occasionally keeps Yakov company, but Yakov is a mostly lonely, sad man. The time period is circa 1911, or the era of Tsarist Russia, shortly before the demise of the Romanovs. After losing his wife, Yakov leaves his village (or shtetl) for Kiev (“the Jerusalem of Russia”) wherein some 50,000 Jews are forced to live in highly restrictive, impoverished districts, as in the case of Podol “where everyone was busy but no one earned much of anything.” Here, we are given a troubled panorama of rotting straw roofs, squalid poverty, and a domed synagogue which has been sacked more than once. The fear of a pogrom is ever-present.

“Yakov, in loose clothes and peaked cap, was an elongated nervous man with large ears, stained hard hands, a broad back and tormented face, lightened a bit by gray eyes and brownish hair. His nose was sometimes Jewish, sometimes not. He had to one’s surprise –after Raisl ran away—shaved off his short beard of reddish cast” (9).

Yakov grew up impoverished in an orphanage (his father had been murdered by drunken Cossack soldiers looking to kill Jews in the streets). He was later conscripted into the Russian army to serve in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), but the fighting was over before he arrived, in his words, “An asthmatic Jew wasn’t worth the trouble.” Then he met Raisl and they married after sleeping together in the woods, but after five and a half years she was unable to conceive a child and ran off. Yakov feels “alive but dead” and he dreams of escaping by boat to Amsterdam en route to America. “All I’ve had in this beggarly town is a miserable existence” (13). He wishes he was born rich; he longs to be educated and read books and learn about the world –in particular, he cannot bring himself believe in the tenets of his Jewish faith and he has grown fond of reading Spinoza. Now desperate for money, Yakov travels out of the Jewish district to the Lukianovsky District –a risky move since Jews are forbidden—and under the assumed name of Yakov Ivanovitch Dolugushev he helps a fat drunken man home who just so happens to be an antisemite (he wears the notorious two headed eagle button). His name is Nikolai Maximovitch. This small act of kindness lands Yakov a job as the overseer of a brickyard and an apartment. As part of his care of the brickyard, he chases a pair of young boys away, and one night, he is very nearly seduced by Lebedev’s daughter, but at the last minute he decides against it since she is menstruating.

Pausing this little narrative for a moment, The Fixer is a tragic tale that reminds us of the abominable legacy of Christian Europe’s infliction of centuries of suffering upon Jews, who were forever regarded as outsiders, foreigners, and irredeemably evil –the result of the “blood libel” theological concept which wrought an unending cycle of cultural vengeance perpetrated upon Jews, who were blamed, as a whole, for the death of Jesus. To be sure, there were small pockets of tolerance and acceptance –as in the case of Alexander I in 1817 and Nicholas I in 1835, who outlawed blood libels against Jews– but these were fairly short-lived pockets in history. In Yakov’s world, fanaticism is once again on the rise as lower-class people across Tsarist Russia are eager to scapegoat their frustrations on Jewish people. Pogroms occur sporadically, and many Christians believe that Jews are the cause of Russia’s woes, that they secretly have hooves, that Jewish men menstruate, that they conduct demonic blood-drinking rituals at night, and that they sneakily stash away rubles so they can rule the world. This kind of vulgar antisemitic superstition, which was rampant throughout Christian Europe, is also rife throughout the pages of The Fixer. In some ways, it actually serves as a sobering reminder of past prejudices, since lamentably –and perhaps shockingly—antisemitism has once again found a footing in our present world.

The following quotation is but one example of the numerous antisemitic conspiracy theories which feature prominently in The Fixer: “God save us all from the bloody Jews… those long-nosed, pock-marked, cheating, bloodsucking parasites. They’d rob us of daylight if they could. They foul up the earth and air with their bloody stink and garlic breaths, and Russia will be done to death by the diseases they spread unless we make an end to it. A Jew’s a devil –it’s a known fact—and if you ever watch one peel off his stinking boot you’ll see a split hoof, it’s true. I know, for as the Lord is my witness, I saw one with my own eyes. He thought nobody was looking, but I saw his hoof as plain as day… Day after day they crap up the Motherland… and the only way to save ourselves is to wipe them out. I don’t mean to kill a Zhidy now and then with a blow of the fist or kick in the head, but wipe them all out, which we’ve sometimes tried but never done as it should be done. I say we ought to call our menfolk together, armed with guns, knives, pitchforks, clubs –anything that will kill a Jew—and when the church bells begin to ring we move on the Zhidy quarter, which you can tell by the stink, routing them out of wherever they’re hiding –in attics, cellars, or ratholes—bashing in their brains, stabbing their herring-filled guts, shooting off their snotty noses, no exception made for young or old, because if you spare and they breed like rats and then the job’s to do all over again. And then when we’ve slaughtered the whole cursed tribe of them –and the same is done in every province throughout Russia, wherever we can smoke them out—though we’ve got most of them nice and bunched up in the Pale –we’ll pile up the corpses and soak them with benzine and light fires that people will enjoy all over the world. Then when that’s done we hose the stinking ashes. Away and divide the rubles and jewels and silver and furs and all the other loot they stole, or give it back to the poor who it rightfully belongs to anyway. You can take my word –the time’s not far off when everything I say, we will do, because our Lord, who they crucified, wants his rightful revenge” (27-28).

One day, the body of a murdered twelve-year-old Russian boy, Zhenia Golov, is found in a cave where it has been stabbed numerous times and drained of blood. As it turns out, Zhenia is one of the boys Yakov once chased out of his brickyard. Naturally, the public is outraged at the boy’s death and the local authorities collectively blame the Jews, claiming the boy was deliberately bled to death as preparation for a Jewish ritual to collect the blood of a Christian child to be used in Passover matzos. Additionally, a vicious, antisemitic gang known as the “Black Hundreds” distributes leaflets bearing their emblem, the Imperial double-headed eagle, and a nationalistic message which reads: “Save Russia from the Jews.”

Very quickly, Yakov is charged and arrested with the murder of Zhenia. From here, he spends the bulk of the novel in prison, contemplating death, life, spirituality, and injustice; while he is tortured, starved, poisoned, frozen, short of breath, verbally abused, hallucinating, in solitary confinement, and physically attacked in all manner of extremely abhorrent, demoralizing ways. He is forced to wear shoes with nails sticking out of them, his clothes are tattered, He is crawling with bedbugs and lice, and he becomes subject to increasing body cavity searches out of a fear that “shifty” Jews are secretly sneaking things into the prison while he is permanently chained to the wall. The warden hopes Yakov will relent and simply confess to the murder, meanwhile the accusations against Yakov and his fellow Jews grow ever more outlandish. The prosecuting attorney against Yakov is an opportunistic bureaucrat who is just looking to get ahead –in his youth he was a passionate “Ukrainophil” but since attaining public office he has become “more Russian than the Tsar.” A notorious Christian priest –Father Anasty—testifies against Yakov, claiming that all Jews are “Christ-killers” who secretly control world events and hide the blood of Christian children in jars for their religious rituals. He is a former Catholic priest who became Orthodox after embezzling funds from Poland. He pushes for renewed pogroms against the Jews, and pens a notorious antisemitic letter in Latin. And if that isn’t enough, Yakov sole ally, Bibikov, is found hanging by his neck in prison.

Suffice it to say, this is a bleak, unforgiving world. It is an extreme version of the Dreyfus Affair. Eventually, Shmuel manages to bribe his way into briefly visiting Yakov in prison, but he soon dies of diabetes. At last his daughter, Raisl, who is still Yakov’s wife, visits and offers him a plea from the prosecution. Yakov has spent about two years in prison by now –all without trial. And Raisl says she gave birth to a child named Chaiml though she claims it’s not all “raisins and almonds” and she simply cannot raise the child by herself anymore. She desperately begs Yakov to claim ownership over the child in order to protect her from scandal, and from the boy being labeled a bastard for life. In a surprising twist, Yakov agrees. Perhaps his limitless compassion has been his own undoing in life. In the end, Yakov is finally granted a trial where he intends to expose Marfa Golov’s gang for the death of Zhenia. While in a carriage en route to the courthouse, Yakov experiences a somewhat ambiguous vision of himself confronting and assassinating the Tsar, acknowledging that he can no longer be politically neutral. In some respects, it shows us the birth of the revolutionary spirit in Russia. Thus ends The Fixer, a remarkably accessible novel for a Pulitzer Prize-winner, but which is nevertheless a difficult book to stomach during vast stretches of utterly brutal suffering.

Lastly, I offer a quotation from the review of The Fixer in The New York Times Book Review in 1966 by Eliot Fremont-Smith: “Through all of his books – four novels and two collections of stories – Bernard Malamud has dealt with the great theme of redemption in this world. The world is grotesque, horrifying and unjust; yet redemption, individual by individual, is possible, is indeed the reason and the glory of life. The redemption of ugliness is in humor, of cruelty in charity, of suffering in consciousness and compassion. The movement of redemption is always from the mass, of fate or the way things unspeakably are, to the person, to individual acts of courage or conscience, to some individual realization that this, too – these tiny but volatile sparks of hope – is part of the way things are, part of what is given. And, by necessity, it makes the rest worth undergoing. This might be called the Judaic factor in the Judeo-Christian outlook, the extra-dogmatic source of the rejection of suicide as a reasonable and ethically viable political act… Mr. Malamud is a superb writer and “The Fixer” is one of the year’s richest novels, a literary event in any season.”

Accusations of Plagiarism and Book-Banning Controversy

The Fixer was based on an infamous case known as the “Beilis case” or the “Beilis trial” of 1913, in which the mutilated corpse of a Christian boy was found in a cave outside Kiev in 1911, and it became the cause célèbre for myriad virulent antisemitic groups to propagate widespread persecution of Jews. A Jewish laborer named Menahem Mendel Beilis was arrested on ludicrous trumped-up charges of ritualistically extracting the child’s blood to be used in Passover matzos and it led to his imprisonment and torture –a prelude to the coming Bolshevik Revolution. Beilis was ultimately acquitted by an all-Christian jury, and he moved to Palestine and then later to New York. Descendants of Mr. Beilis have continued to allege that Malamud plagiarized his novel from Beilis’s 1925-1926 memoir entitled The Story of My Sufferings, including a 2011 edition of Beilis’s memoir, Blood Libel: The Life and Memory of Mendel Beilis, which was co-edited by one of Beilis’s grandsons (Jay Beilis) and which claims to have identified at least 35 instances of plagiarism by Malamud. In his 2007 biography of Malamud, Bernard Malamud: A Writer’s Life, Philip Davis noted similarities between the two works, however that Malamud’s novel is ultimately unique and that Yakov is notably different from Beilis. Neither in The Fixer nor in any public statements, did Malamud ever acknowledge the great debt he owed to Beilis’ book.

Additionally, The Fixer has long been a banned book at various points in American history. It was banned from a school in New York which eventually led to a Supreme Court case in 1982. More recently, in the new era of right-wing censorship, in 2022 The Fixer was removed from a school district in South Carolina due to dozens of parental complaints requesting all manner of books be canceled from the district. However, after further review in 2023 and amidst ongoing controversies, the book was eventually returned to the library. However, it is still listed on conservative sites warning parents of the book’s content. Why it was ever considered for removal, I couldn’t exactly say. In my view, censoring a book like The Fixer is about as silly as it gets.

Notable Quotations

“From the small crossed window of his room above the stable in the brickyard, Yakov Bok saw people in their long overcoats running somewhere early that morning, everybody in the same direction” (3, opening lines).

“Don’t talk to me about charity. What have I had all my life? What have I got to give away?” (6).

“I fix what’s broken –except in the heart” (7).

“All I’ve had in this beggarly town is a miserable existence” (13).

“The Russians make pogroms against the Russians –it went on throughout their history. What a sad country, he thought” (60).

“I’m a fixer but all my life I’ve broken more than I fix” (104).

“He felt entrapped, abandoned, helpless. He had disappeared from the world and nobody he could call friend knew it” (155).

“There’s something cursed, it seems to me, about a country where men have owned men as property. The stink of that corruption never escapes the soul, and it is the stink of future evil” (172).

“He sank into deep gloom. I’ll be here forever. The indictment will never come. I can beg on both broken knees but they won’t give it to me. They will never bring me to trial” (195).

“’You can deny it all you want, we know the truth,’ Grubeshov shouted. ‘The Jews dominate the world and we feel ourselves under their yoke. I personally consider myself under the power of the Jews; under the power of Jewish thought, under the power of the Jewish press. To speak against the crimes of the Jews means to evoke the charge that one is either a Black Hundred, an obscurantist, or a reactionary. I am none of these things. I am a Russian patriot! I love the Russian Tsar!’” (226, one of many examples of antisemitism throughout the novel).

“One thing I’ve learned, he thought, there’s no such thing as an unpolitical man, especially a Jew. You can’t be one without the other, that’s clear enough. You can’t sit still and see yourself destroyed” (335).

On the 1967 Pulitzer Prize Decision

According to former Pulitzer Prize administrator John Hohenberg, in his sweeping history of the Pulitzer Prizes, the 1967 Fiction Jury stated the following in its jury report: “The jury recognized the fact that in an age notable for novels of self-pity, Mr. Malamud has taken the raw material of still another victim –or an ‘anti-hero,’—and turned him into a heroic figure: twentieth century and authentic. With a kind of wry passion, Malamud denies the modern paralyzing fear that personal goodness cannot survive the evil of history; and in doing so brings to the American novel a new and tough sense of possibility.” Other books mentioned in the Jury Report included: Fertig by Sol Yurick, The Last Gentleman by Walker Percy, The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon, Strangers and Graves by Peter Feibleman, Giles Goatherd by John Barth, and Nothing Ever Breaks Except the Heart by Kay Boyle. Others considered were works by John O’Hara, Kenneth Rexroth, John Hersey, V. Nabokov, James Farrell, William Maxwell, and Conrad Richter.

Upon being notified that he had won a Pulitzer Prize, Malamud was initially in doubt, primarily because he thought the novel’s foreign setting disqualified it from winning the prize, but he was also somewhat unimpressed with the Pulitzer Prizes. He had already won two National Book Awards (for The Magic Barrel in 1959 and The Fixer in 1967) and held those awards in higher esteem than the Pulitzer, which failed to honor Saul Bellow and Eudora Welty for the prize.

In his other book, The Pulitzer Diaries, John Hohenberg also noted there were several laureates of this era who held little respect for the Pulitzer Prize, such as dramatist Edward Albee who thought the awards were a “declining honor” because his best play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? had been slighted, and Arthur Miller stated that the award typically “comes to those who do need it.”

The 1967 Fiction Jury was composed of the following three members (notably, the jury composition returned to its standard of three members after many years of two-person juries):

- Maxwell Geismar (1910-1979) was a Columbia University alumnus and teacher at Harvard who became a famous literary critic for a variety of publications including The New York Times Book Review, The New York Herald Tribune, The Nation, The American Scholar, The Saturday Review of Books, The Yale Review, The Virginia Quarterly, Encyclopedia Britannica, and Compton’s Encyclopedia (he also penned a notoriously belligerent critique of Henry James).

- Melvin “Mel” Maddocks (1924-2008) was a literary critic for the Christian Science Monitor. He also wrote for The Atlantic in the late 1960s and early 1970s, contributing reviews of Proust, Hamlet, Cyril Connolly, among other articles. Maddocks penned a variety of books on topics like Claude Debussy, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Billie Holiday, and The Atlantic Crossing. He married Jean Lister in the photo department at the Monitor and they had two sons and a daughter (and eventually one grandson).

- Elizabeth Janeway (1913-2005) was a bestselling novelist, book reviewer for The New York Times (where she famously defended Lolita) and a judge for the National Book Awards in 1955 as well as for the Pulitzer Prize in 1967 and 1971. She was an executive of International PEN; president of Author’s Guild (1965-1969); a longtime member of the executive board of the American Center of Poets, Essayists and Novelists; a member of the board of directors of the McDowell Colony; and a judge for both the National Book Awards and the Pulitzer Prizes. She was a trustee of Barnard College (her alma mater), a fellow of Berkeley College at Yale University and a director of the Legal and Education Fund for the National Organization for Women. She was married to economist, Eliot Janeway, who was an influential advisor to both Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson (and also a critic of U.S. economic policy from FDR to Reagan). They had two sons.

The early Pulitzer Prize for Fiction was somewhat reticent to award the prize to books that took place abroad, in foreign contexts that were not directly related to the American experience, however other earlier examples aside from The Fixer included The Bridge of San Luis Rey, The Good Earth, The Old Man and the Sea, and A Fable.

Who is Bernard Malamud?

Bernard Malamud (1914-1986) was born in Brooklyn, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants (his father Max Malamud ran a small grocery store). Malamud received a BA from New York City College in 1936 (via a government loan), and a master’s degree from Columbia University in 1942 (his thesis was on Thomas Hardy). Malamud then worked various odd jobs, such as in a factory as well as the Census Bureau. He was excused from military service during World War II as a result of his support for his widower father. Malamud’s brother, Eugene, suffered significantly from mental illness and led a lonely life until his death in his fifties. Bertha Malamud (mother of Bernard and Eugene) also suffered from severe mental illness – she was “emotionally unstable” and attempted suicide by swallowing disinfectant in 1927. Bernard found her and saved his mother’s life, but she died in a hospital two years later.

Starting in 1949, Malamud taught composition at Oregon State University (ending his tenure in 1961), an experience he fictionalized in his 1961 novel A New Life. While at OSU, Malamud devoted three days out of every week to his writing, and in 1961, he left OSU to teach creative writing at Bennington College in Vermont (he also briefly taught for two years at Harvard). In 1952, Malamud published his first novel The Natural (1952), which was about a baseball prodigy (it was made into a 1954 film starring Robert Redford), and this was followed by The Assistant (1957), which was about a trio of immigrants in Brooklyn in the 1950s. It was his first finalist for the National Book Award and it was later made into a film in 1997. With publication of The Assistant and The Fixer, Malamud began to be regarded as a Jewish writer on par with Saul Bellow and Philip Roth Malamud then published a semi-autobiographical campus novel entitled A New Life (1961), and then The Fixer (1966) which won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. His next book Pictures of Fidelman: An Exhibition (1969) was a short story cycle about an aspiring painter who travels to Italy. His final three novels were: The Tenants (1971), Dubin’s Lives (1979), and God’s Grace (1982). Apparently, his later works received mixed reviews; they were often criticized for a sense of bleakness and for being excessively academic in tone. He also published a variety of short story collections throughout his career, beginning with The Magic Barrel (1958), which won his first of two National Book Awards.

In 1967, Malamud became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In addition to winning the Pulitzer and a National Book Award, he also won a Rosenthal Award from the National Institute of Arts and Sciences, Vermont’s 1979 Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, and the 1981 Brandeis Creative Arts Award.

In 1942, Malamud met Ann De Chiara (1917-2007), an Italian-American Roman Catholic, and a 1939 Cornell alumna. They married in 1945, in spite of the opposition of both of their parents (Ann was not Jewish but throughout Malamud’s writing career, she served as his chief typist and editor). They had two children, Paul (b. 1947) and Janna (b. 1952). Janna later wrote a memoir about her father entitled My Father Is A Book.

Malamud was reportedly Jewish, agnostic, and a humanist. He once described himself as a chronicler of “simple people struggling to make their lives better in a world of bad luck.” Malamud died in Manhattan on March 18, 1986, at the age of 71. He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On the career of Bernard Malamud, fellow writer and Pulitzer Prize-winner Philip Roth remarked: “What it is to be human and to be humane, is his deepest concern.” On the 100th anniversary of Malamud’s birth, a three-volume collection of his works was announced by the Library of America.

Film Adaptation:

- The Fixer (1968)

- Director: John Frankenheimer (screenplay by Dalton Trumbo)

- Starring: Alan Bates, Dirk Bogarde, Georgia Brown

- Director: John Frankenheimer (screenplay by Dalton Trumbo)

Literary Context in 1966-1967

- Nobel Prize for Literature (1967): Guatemalan writer Miguel Ángel Asturias.

- National Book Award Winner (1967): The Fixer by Bernard Malamud.

- Per Publishers Weekly, the #1 bestseller in 1966 was Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann. From a friend she obtained a list of the bookstores on whose sales figures The New York Times relied for its bestseller list, and then used her own money to buy large quantities of her book at these stores, causing it to head the list. Other notable books on the list that year included: Capable of Honor by Allen Drury, Tai-Pan by James Clavell, All in the Family by Edwin O’Connor.

- The Roman Curia abolished the Index Librorum Prohibitorum of books banned by the Catholic Church, after 427 years.

- Octopussy and The Living Daylights was published, the final collection of James Bond short stories by Ian Fleming, who died in 1964.

- American poet and critic Frank O’Hara was hit by a dune buggy on Fire Island beach. He died of his injuries the following day.

- The first UNESCO International Literacy Day was celebrated.

- Tom Stoppard’s tragicomedy Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead was first performed.

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita first began to be published.

- Cancer Ward by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was first published.

- Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys was published.

- The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon was published.

- Last Picture Show by Larry McMurtry was published.

- Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes was published.

- The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress by Robert A. Heinlein was published.

Did The Right Book Win?

Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer is a remarkably accessible novel –it is plainly written and still remains darkly compelling, even as Yakov undergoes every form of scorn and torment known to man—however, the book nevertheless borders on being grotesquely exploitative and even a bit tedious during its endless scenes of horrid imprisonment.

Also, I tend to be at least partly suspicious of novels that seem to be aggressively invoking the feeling of pity in their readers. Too much pathos and not enough logos makes for an unsatisfying story in my view, and at certain points, The Fixer runs the risk of opening this door. And while The Fixer is assuredly not on par with the weighty, existentialist novels of Dostoevsky, nevertheless the book does make an effort to engage in a philosophical dialectic over questions of religion, justice, prejudice, and the possibility of political neutrality in a morally decaying world.

For the 1967 Pulitzer Prize, Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 would have likely been a more suitable literary selection, however in my view The Fixer is a perfectly fine enough winner of the prize, resting comfortably somewhere in the middle of pack of the Pulitzers I have thus far encountered. It seems a stretch to rank it anywhere near the best of the winners, but I still appreciated this rare opportunity to learn more about 20th century antisemitism and the historical case of Mendel Beilis. And today, in an age of rising antisemitism coupled with Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, The Fixer serves as another strangely timely book.

Malamud, Bernard. The Fixer. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. New York, NY (1966). I am grateful for yet another opportunity to read a first edition copy of a Pulitzer Prize-winner.

Click here to return to my survey of the Pulitzer Prize Winners.