In a note at the beginning of Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” we are presented with an old Masai legend which tells of a frozen leopard that lies near the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro. No one knows how the leopard got there or where exactly it is located. The frozen leopard has actually been spotted several times over the years, once by a Lutheran missionary in 1926 above 18,000 feet, and again the bones were spotted in 1997.

In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” Hemingway introduces us to Harry, a writer who is dying of gangrene at a remote camp while on safari in Africa. He is joined by his wealthy paramour, a widow named Helen. As the story unfolds, we learn about their complex relationship. During the safari Harry has been unfortunately scraped by a thorn while taking a photo, and forgetting to immediately put iodine on the wound, his leg has become gangrenous. He knows that he is dying.

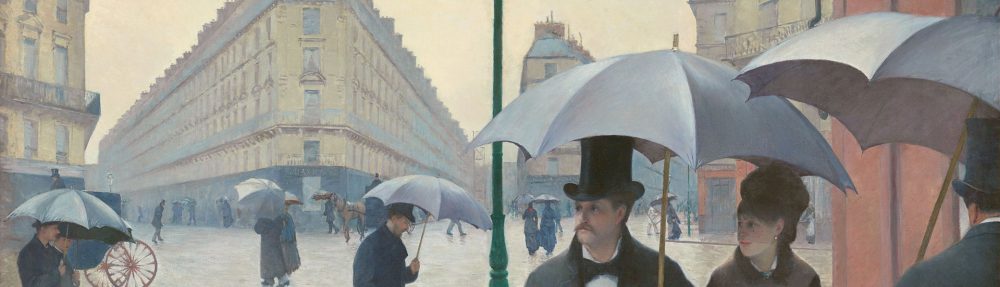

Harry’s mortal leg wound serves as a metaphor for his own decay in his relationship with Helen. Harry resents Helen for her wealth which he claims has prevented him from writing. He treats her poorly throughout the text. And now that he is facing death, he has nothing but his own memories for comfort in the night. A hyena howls off in the distance, signifying Harry’s imminent death. Soon, he experiences the stench of death all around him. His leg wound also reminds him of his forgotten former life (parallels abound to Hemingway’s other famous wounded protagonists like Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises as well as Frederic Henry in A Farewell To Arms). In a series of fascinating flashbacks we receive glimpses of Harry’s past: his first love, travels throughout Europe, his life in Paris, fishing, war, and so on. The reflections are some of the most beautiful passages in the story.

The story opens with Harry marveling at the painlessness of life when death is imminent. He is aware of his own fate (i.e. he is not a tragic figure like Oedipus). He is somber and disgruntled at his own feeling of placelessness –he feels out of place with respect both his relationship with Helen, and his purposelessness as a writer. At the end of the story, Harry gives up the ghost while receiving a vision of being airlifted to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro to die.

The selection of the location as Mount Kilimanjaro points us, once again, to the idea of placelessness in the story –Kilimanjaro is the largest mountain in Africa and it rises out of northern Tanzania. Geographically, the mountain seems out of place because it rises high over the plains, and it is snow-capped, while the surrounding region is a dry, low-lying plain. Mount Kilimanjaro seems strangely out of place to the naked eye. Like the mountain, and like the leopard that lies frozen near its peak, Harry is also out of place. He is a writer who does not write, he is a married man who does not love, and he is dying with soon-to-be-forgotten recollections of an extraordinary life well-lived. Perhaps Hemingway points us to a certain restlessness that is natural to the human experience, or at least as natural as leopards and mountains which appear in seemingly unusual places.

“The Snows of Kilimanjaro” was first published in August 1936 in Esquire Magazine at the same time that “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” was published in Cosmopolitan Magazine.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Short Stories. New York, Scribner, 1955.