“Although in our time democracy is taken for granted, it is in fact one of the rarest, most delicate and fragile flowers in the jungle of human experience” (2).

Donald Kagan’s biography of Pericles explicitly purports to portray Pericles as a man of “heroic qualities” who was “a powerful force that significantly shaped not only his own times but centuries to come.” Throughout the book, Kagan argues that Pericles represents a hero of the modern era –an enlightenment rationalist, a defender of democracy, a peacemaker, strategist, and great patron of the arts. However, crafting a nuanced is a tricky task for a man of the fifth century BC who left behind no speeches, letters, nor any other writings. Our primary source on the life of Pericles comes down to us from Thucydides and a few other ancient writers like Aristophanes and Plutarch (writing some five centuries later). In this fascinating “counterfactual history,” Kagan shows threads of Pericles found in 20th century leaders like Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

In addition, Pericles’s legacy can be found in the halls of American democracy as well as the British Empire (particularly Elizabethan England), along with Lorenzo de’Medici or even Augustus in Rome, and even Voltaire identified Periclean Athens one of the four societies that enjoyed incomparable greatness, the others being Caesar’s Rome and Augustus, Italy during the fifteenth century Renaissance, and France under Louis XIV. And since the story of Pericles is inseparable from the cultural rise of Athens, Kagan’s book is also an examination of 5th century BC Athens. A brief history traces the growth of Mycenean kingly civilization and the explosion of a literate, seafaring people around the Mediterranean. And while the Homeric era became the source of cultural education for the ancient Greeks, the unique character of Athens emerged out of Solon and Cleisthenes instituting reforms and abolishing the Peisistratos tyranny. Here comes the desire to celebrate and preserve the bloodlines of the ancient aristocratic families, the emergence of Archons as magistrates of the city, their graduation to the areopagus, the Council of 500, the rise of law courts as popular entertainment, and also new practices like political ostracization (a ten-year exile for perceived enemies of the city).

Kagan spends a great deal of time reiterating Herodotus’s account of the Persian Wars and the subsequent effusive triumphal aftermath in Athens which yielded an exuberantly wealthy city based on the principal of self-governance for all male citizens. And it was this rise of Athens that led to conflict with the other great military power, Sparta –Athens having naval supremacy of the seas, and Sparta having an unmatched landed cavalry. In the wake of the Persian Wars, the chief politician in Athens was Cimon, one of the chief architects (strategoi) of the Greek victory over Persia, especially at the Battle of Salamis. He led the formation of the Delian League and experienced continued victories over Persia and also oversaw the devolution of the Delian League from its initial conception as a multi-polis peace-making alliance, into a powerful extension of the Athenian Empire. Eventually, Cimon lost the support of the Athenian people when he convinced the Assembly to send military to aid to Sparta during a revolt of the helots. At the time, Cimon (son of Miltiades of the wealthy Philaid clan) was seen as a defender of the old guard aristocracy, and he was friendly with Sparta who viewed him with respect, even though many Athenians held a certain degree of contempt for Sparta for its perceived lack of commitment during the Persian Wars. At any rate, Cimon’s aid to Sparta was inexplicably refused and he was snubbed –the ensuing embarrassment led to his ostracization and the arrival of Pericles on the scene.

Unlike Cimon, Pericles was a far more democratic figure in Athenian politics. He celebrated the elevation of the common man. Kagan argues that the populism of Pericles allowed for a maturation of 5th century Athenian democracy (which at the time had a population of perhaps 250,000). Thucydides reports that Pericles own summary of the qualities necessary for statesman were: “to know what must be done and to be able to explain it; to love one’s country and to be incorruptible.” Pericles is only brought into Thucydides narrative a mere three years before his death. Pericles was a patron of the arts, a producer of Aeschylus’ tragedy Persians. He was a friend of Sophocles, and the great sculptor Phidias who drafted the master plan for the Parthenon. Pericles commissioned Hippodamus of Miletus, the first city planner, and he was a friend of Herodotus.

According to legend, at about 494 BC a pregnant Agariste dreamed she would give birth to a lion, and in a few days she presented her husband Xanthippus with a son named Pericles (Herodotus recounts this story). At the time, Athenian democracy was only about a decade old, with Agariste’s uncle Cleisthenes being its founder. Her family, the Alcmaeonids, may have been the most powerful in Athens, and could apparently trace their lineage to the Homeric character, Nestor. When Pericles was four years old, the battle of marathon took place and his father Xanthippus almost undoubtedly fought in it. In a rivalry with the great Athenian General Themistocles, Xanthippus was ostracized in 494 BC but soon returned to fight Persia. After the war, Themistocles himself would face ostracization for the controversial construction of walled fortifications around Athens.

Pericles made his first major political appearance in 463 BC at the age of thirty-one, a late start for an aspiring Athenian politician. This was a politics that centered on individuals rather than parties or factions, such as “those around Themistocles” or “Cimon and his friends.” Athletic prowess was the gateway to wealth and political power, it was proof of one being a superior man.

Following the aftermath of the Persian Wars there was a gradual breakdown in the Panhellenic spirit: “The triumph of democracy in Athens produced a sharp change in the city’s foreign policy and unleashed a war that threatened the new regime” (65). Cimon sought to preserve the union, but the growing wealth and might of Athens led to a fear of the city’s increasing boldness and its revolutionary spirit. Athens encouraged democratic revolutions in most of its allies –a practice that was not always welcome for the older generation of Persian War heroes. When Pericles ascended to the “first citizen” of Athens, he began passing the most democratic reforms the world had ever seen –direct power to citizens within the assembly as well as the law courts through simple vote majorities, public offices were selected by lot, he limited citizenship rules such that both parents needed to be Athenian-born, he encouraged the popular law courts within the context of the burgeoning commercial atmosphere and a rising litigious democratic spirit. Payments were made for service in law courts, and payments were made for other forms of public service, as well. The character of the city was rapidly changing and with it, the Athenians were changing, too.

During a tenuous peacetime, with a conflict in Cyprus (where Cimon later died), a conflict against the Persians in Egypt, and proxy wars against Corinth, Athens began to act recklessly, confident in its own supremacy. The popular narrative of boundless success and endless victories had given Athens tremendous pride and jingoism, but with it came a new spirit of recklessness and tolerance for risk. Such is the hubris of empire.

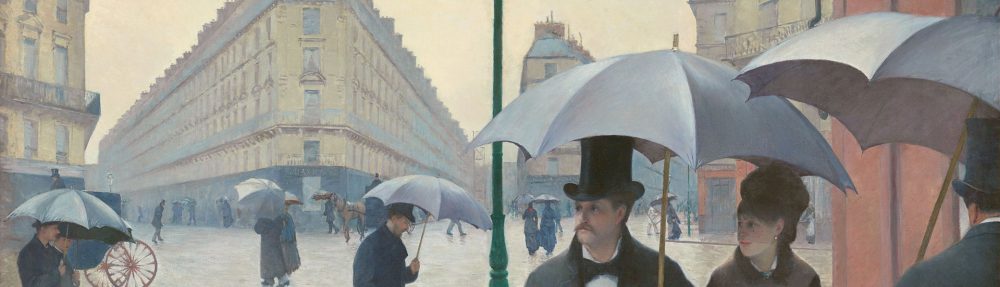

In Kagan’s discussion of the Periclean architectural boom, Kagan offers a helpful, lengthy description of the crown jewel of Athens: The Parthenon. The Athenians were constructing a temple to the warrior goddess on the southside of the acropolis, alongside the old temple to Athena Polias on the north, when the Persians invaded and leveled both shrines. Notably, when Pericles undertook to restore the sacred buildings on the Acropolis, he did not begin with the shrine to Polias, the traditional focus of Athenian worship, but rather with a building dedicated to Parthenos under the direction of Phidias. Like all temples built west of the Aegean the Parthenon was Doric, though it was complicated by a complex plan with Ionic elements. The interior sculptures were sadly damaged or destroyed in 1687 when a German gunner in the Venetian service hit the Parthenon, which was serving as a Turkish powder magazine. Scholarly debate over whether it was essentially a religious in nature –it surely had pious elements but also served as a treasury and as an elaborate ornament, Kagan argues it represents the fulfillment of Pericles’s Funeral Oration speech. It might be best regarded as an “offering consecrated within a place of worship.” It was an offering to Athena in gratitude for victory over the Persians, but it was also a tribute to the people of Athens in celebration of a city of earthly delights. Upon viewing it, one is immediately drawn to the frieze atop the Parthenon which Kagan argues represents a new piety for reason rather than the religious superstitions of the masses. It’s worth mentioning that ancient religious activity in Athens was not centralized according to modern religions like Christianity or Judaism, but rather there were a series of cults and gods all geared toward the patriotic devotion to the city. Kagan portrays Pericles’s apotheosis of “rationalism and enlightenment” as radical for the time.

Pericles’s marriage produced two sons, Xanthippus and Paralus, until it ended in divorce. And his sons apparently were somewhat troubled afer the fact, with a fraught view of their father. Pericles then took on guardianship of Cleinias and Alcibiades. He spent the remainder of his days with Aspasia, a trusted erotic lover and companion, with whom he had another son, Pericles the Younger. Rumors swirled that Pericles had been ensnared by this temptress, and other friends became swept up in his political scandals, such as Phidias who faced scrutiny over the funding of his gold-plated statues in the Parthenon. Rumors began to emerge that Pericles might be likened to an impious figure and a tyrant.

In time, Pericles was criticized for corrupting the city and bribing the masses for public service and using democratic reforms to increase his own power. It was alleged that he was a democrat in name only who ruled the people benevolently but firmly. It didn’t help that his visage resembled the ancient tyrant, Peisistratos. At the same time, the Delian League was increasingly under the control of Athens while the Peloponnesian League was led by Sparta. At its height, Athens’s navy controlled a stretch of geography from Sicily to the Nile delta, and the armies controlled central Greece and access to the Peloponnesus. It had alliances with Argos, Sparta’s neighbor and bitter enemy, and the Thessalians in northern Greece famed for strength and excellence of the cavalry, while Sparta was allied with Megara and Corinth who were in conflict over a border territory which Megara lost. Megara was a key strategic point on the isthmus while Corinth was a cultural and wealthy center of power (hosted the Isthmian Games, one of the four great religious-athletic festival in the Greek world, as well as the impressive Temple of Aphrodite). It was a center of trade and commerce with an extensive network of allies. Thus, when Megara defected and formed an alliance with Athens, it brought Athens directly in conflict with Corinth, a conflict now known as the “First Peloponnesian War.” During the fighting, Athens gained wide swaths of mainland Greece that threatened its neighbors ultimately culminating in a massive Spartan invasion of Athens and the fighting concluded with the Thirty Years Peace which granted permission for both Athens and Sparta to operate their own alliance networks in relative peace without disrupting the other.

This was the pretext to open warfare which soon broke out with a rebellion in Samos against Athens (which was now collecting tribute and storing it in the newly constructed Parthenon). The lives lost in the Samian War was the context in which Pericles delivered his famous Funeral Oration speech. And with an unpopular imperial policy, the Delian League continued to devolve into an empire. However, Pericles initially celebrated the empire as an extension of Athenian pride and greatness. He envisioned a new kind of state, where aesthetic and intellectual greatness could flourish, wherein Athens was to be the “educator of Greece” and this vision required a vast commercial empire. But with continued vulnerabilities from land armies, Athens essentially abandoned its farms to live within the constructed city walls and they outsourced food production. Here, we can see the contrast between the defensive placid immobile character of the Spartans contra the aggressive and dangerous character of the Athenians. Sparta sought rigid consistency, while Athens took great risks to preserve its rising standard of living. Athenians were prized for thoughtful deliberation and discussion; the Spartans were famous for their brevity and distrust of subtle reasoning

As the war is re-ignited and Athens is blamed for breaking the peace, Kagan offers a nice tour of ancient Greece with the culture and character of each major polis while also describing tensions with Argos, conflicts with Corinth, and Boeotia (a central landlocked region the Athenians apparently regarded as little more than country bumpkins), along with rebellions in smaller cities like Elis, Epidaurus, Aegina, Miletus, Corcyra, Megara, Potidaea and Mantinea. “The last thirty years of the century were terrible times of war, plague, impoverishment, and defeat. Yet neither during or after the war did the Athenian interfere with private property or seek economic leveling” (62).

But as the war dragged on, the fortunes of Athens sank –the wealth of Athens was blunted by the tribute and taxation in order to pay for offices (since Athens elected to pay for civic service, rather than operating on the basis of civic virtue alone, which had characterized past generations). Additionally, a horrid plague utterly devastated the citizenry of Athens (perhaps a result of outsourcing food production to far-away lands). The result was widespread misery and despair, as well as the ascendance of a kind of nihilism as wild conspiracies erupted among the people of Athens. And as the flower of Athens decayed, so did the personal life of Pericles. In the last two years of his life, his eldest son became estranged, both legitimate sons died of the plague (as well as his sister), and he was forced to ask the Athenians for a special exception to the Athenian citizenship for his bastard son. The perception of Pericles was of an arrogant haughty man, meanwhile he watched as Athens’ wealth evaporated, it continued to outsource its grain supplies, and was tragically pitifully reduced by war and disease. Pericles was forced to lament that the tyrannical empire of Athens may have been wrong to acquire but now it was too dangerous to let go. He became subject of scrutiny by his political opponents, like Cleon. His fate could be seen in Sophocles’s staging of his masterpiece Oedipus Tyrannus on the slopes of the acropolis in the spring of 425. When Pericles died, he was widely mourned for every leader wo came after him strove for popularity –feeding the people’s appetites—rather than governing with prudence.

In the ongoing debate over Pericles’s legacy –was he an imperialist demagogue, or peace-loving democrat?– Kagan joins forces with the defenders of Pericles as a noble hero of the Golden Age of Athens, rather than a catalyst and accelerant for the city’s decline. Of course, there is a third option not discussed. Perhaps a figure like Pericles represents two things at once: he is both the apex of Athenian flourishing and power, and therefore also its moment of decline. But this would require a theory of the polis which suggests it can only ever rise and fall, never plateau. At any rate, I will close this humble review with an early quote from the book wherein Kagan links the legacy of Pericles to our post-Cold War age:

“If the new democracies of our time are to succeed, they too must offer more than economic prosperity. The task of their leaders will not be easy, for their people have become cynical about idealism of any kind. Like Pericles, however, they will need to give their people a noble vision that offers spiritual as well as material satisfaction so that they, too, will acquire the devotion their democracies need to carry them through the difficult challenges they will face” (10).

Kagan, Donald. Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy. The Free Press, a division of Macmillan, NY, NY (1991).