For Whom The Bell Tolls was supposed to win Ernest Hemingway his first Pulitzer Prize in 1941. However, like Sinclair Lewis before him, the prize was denied by the controversial President of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler. As the story goes, the 1941 Novel Jury recommended several books for the Pulitzer Prize including, but not primarily, For Whom The Bell Tolls. Upon receiving the Jury’s recommendations the Pulitzer Advisory Board favored the critic’s choice For Whom The Bell Tolls. However, before the Board could complete a vote on the matter they were blocked by one man: Nicholas Murray Butler. He objected to the ‘lascivious’ content in the novel (Sound familiar? Nicholas Murray Butler also blocked the Pulitzer Prize from being bestowed upon Sinclair Lewis in 1921 for his novel Main Street, and instead, the 1921 prize was awarded to Edith Wharton for The Age of Innocence).

Why did no member of the Pulitzer Advisory Board stand up to Nicholas Murray Butler? How was he able to railroad the whole process? His story is worth mentioning as he was a fascinating American figure. Nicholas Murray Butler was viewed as something of an autocratic ruler at Columbia University, often wantonly dismissing staff and faculty, pushing for a distinctly pro-America atmosphere on campus, prohibiting entry for Jewish students –in a word, he ruled Columbia with an iron first, and yet he was also a respected American statesman. He was the former running mate of William Howard Taft in the Presidential election of 1912, and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 along with Jane Addams, for his humanitarian efforts as President of the Carnegie Endowment For International Peace. He helped to negotiate peace in Europe using elite relationships he cultivated with leaders like Kaiser Wilhelm II. Nicholas Butler Murray was also a popular cultural figure. Each year The New York Times printed his annual Christmas Greeting to the nation. He is recognized today as the longest serving President of Columbia University (43 years), a tenure which first began in his role as Interim President in 1901 before he was officially elected President of Columbia, serving from 1902-1945. So when Nicholas Murray Butler stood in the doorway of the Pulitzer proceedings refusing to move or relent on the Hemingway question while shouting “I hope you will reconsider before you ask the university to be associated with an award for a work of this nature!” –no one dared to stand against him. The full details of the confrontation were later brought to light in 1962 by Arthur Krock, the celebrated New York Times journalist and Pulitzer Board member at the time. As a consequence of the fight, no novel was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1941.

That year, the Novel Jury welcomed a newcomer, best-selling novelist Dorothy Canfield Fisher, to replace Robert M. Lovett from the previous year. Dorothy Canfield Fisher is perhaps best known for being ardent social activist, a tireless advocate of education. She helped bring the Montessori School system to the United States, but she also achieved other important cultural milestones. She was praised by Eleanor Roosevelt as one of the most influential women in America. Alongside Fisher, two veteran Novel Jury members also reprised their roles on the Jury in 1941: Jefferson B. Fletcher (Literature Professor at Columbia University), and Joseph W. Krutch (Literature Professor at Columbia University and naturalist writer). For the Pulitzer Prize in 1941, this trio also considered several other novels aside from For Whom The Bell Tolls including The Trees by Joseph Conrad, The Ox-Bow Incident by Walter Van Tilburg Clark, Native Son by Richard Wright, and Oliver Wiswell by Kenneth Roberts. The Jury apparently favored two coequal novels for the prize: The Trees by Joseph Conrad and The Ox-Bow Incident by Walter Van Tilburg Clark, and chairman Krutch went so far as to critique Hemingway’s For Whom The Bell Tolls for its “romantic sensationalism” and for having “a style so mannered and eccentric as to be frequently absurd.” However, the newspapermen of the Pulitzer Advisory Board rejected this snub and unilaterally selected For Whom The Bell Tolls until a fiery Nicholas Murray Butler blocked its nomination.

Of course, despite being robbed the first time, Hemingway later won the coveted Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for The Old Man And The Sea (feel free to read my reflections on The Old Man and the Sea here).

For Whom The Bell Tolls is as tense a novel as it is tender. It is the story of love and war -a soldier’s duty contrasted with a lover’s embrace. The book takes us covertly behind enemy lines during the destructive Spanish Civil War of the 1930s (a war which lasted from 1936-1939). The book spans approximately four days, and within that narrow timeframe a lifetime occurs: we gain a profound and complex glimpse into the nature of heroism and cowardice among ordinary people. Amidst the chaos of war and the looming specter of death, For Whom The Bell Tolls also pulls back the curtain on a budding romance between an American soldier and an innocent Spanish girl.

For context, during the Spanish Civil War, battle lines were drawn between a coalition of conservatives, nationalists, and Catholics, led by the military dictator Francisco Franco; and on the other side, a loose-knit federation of republicans, liberals, communists, and anarchists. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy supported Franco, while Soviet Russia and Mexico supported the communists, but the United States, England, and France maintained a public stance of neutrality. After years of violence in every major Spanish city, the Spanish Civil War was eventually brought to an end in 1939 with the fascists taking over the country under Francisco Franco. During the war writers like George Orwell pleaded with the West to support the republicans against the fascists (see Homage To Catalonia). The war was later dubbed a “dress rehearsal” for World War II by Claude Bowers, U.S. Ambassador to Spain.

In the novel, Hemingway introduces us to Robert Jordan, a Montana-native and Spanish language professor. Robert Jordan has unfortunately found himself in the midst of the Spanish Civil War while on leave in Spain during the outbreak of the war. He is a volunteer in the International Brigades (a international coalition of fighters organized by communists). During this time Robert Jordan has become an experienced soldier and dynamiter. He is tasked with destroying a key strategic bridge inn order to block supplies and munitions from reaching the fascists through the Sierra de Guadarrama. The order comes from Golz, a Soviet officer.

En route to complete his mission, Robert Jordan encounters an old man named Anselmo who takes Robert Jordan high up into the mountains outside Segovia in central Spain (north of Madrid) where a band of guerrilla warriors is hiding out in a cave from the fascists below. While there, Robert Jordan meets Pablo, a jaded rebel who once led the revolt against fascism but now spends his time ignobly drinking wine and sarcastically deriding the war. He also meets Pablo’s wife, Pilar, a strong-willed woman who serves as the de facto leader of the group in Pablo’s abdication (“Pilar” was a nickname for Hemingway’s third wife, Pauline, and also the name of his fishing boat); a gypsy named Rafael; and several other soldiers like Agustín, El Sordo, Fernando, Andrés, Eladio, Primitivo, and Joaquín. The group exists there by a “miracle” according to El Sordo. The fascists are unaware of their presence. The group quickly grows accustomed to Robert Jordan and they call him “Inglés” or simply “Roberto” (the whole novel is rife with Spanish idioms, including edited obscenities). However, the people in the cave are strange and unfamiliar. All throughout his days in the cave the reader asks: can Robert Jordan really trust these guerrilla fighters? How can we be certain they are not going to sabotage the mission?

The most important character Robert Jordan meets in the cave is María, a young Spanish girl whose town was ravaged by the fascists. She taken alive by the fascists -her hair was hacked off and she was raped, but she was then rescued and cared for by Pilar. Robert Jordan and María quickly strike up a romance, and Pilar essentially gives María to Robert Jordan as his lover with the promise of marriage. Robert Jordan calls María his little “rabbit” and they spend most evenings together in Robert Jordan’s sleeping bag just outside the cave.

While introducing us to the tenderness of Robert Jordan’s new love, the first half of the novel also delivers an extraordinarily tense series of moments. The impending mission to destroy the bridge plagues the reader’s mind. Will the weather be good? Will the fascists retaliate? Will they find the cave before the bridge can be blown? Will Golz call off the mission? Who will die? Who will live? Filled with hope and worry, Robert Jordan hides out with the rebels in the mountains while trying to keep a low profile, careful about what information he reveals. At the same time, skepticism grows regarding Pablo’s loyalties, and Robert Jordan places his faith in Pilar.

Suddenly, Robert Jordan is surprised one morning when an unsuspecting fascist patrolman stumbles onto his outdoor sleeping bag. Robert Jordan quickly leaps up and kills the patrolman. Then a skirmish breaks out across the mountain killing El Sordo’s entire band of fighters. Robert Jordan and the remaining fighters wait a day, and then assault the bridge (undeterred by a momentary lapse of judgment from Pablo when he steals some of Robert Jordan’s explosive equipment in the night, casting it into a ravine. Pablo eventually rejoins the fight in an effort to redeem himself). As the group approaches the bridge, they quietly kill the fascist sentries. Robert Jordan and the old man Anselmo then successfully wire, detonate, and destroy the bridge, but the explosion kills Anselmo along with several others in the process. The remaining guerrillas flee back up into the mountains having completed their mission.

“Dying was nothing and he had no picture of it nor fear of it in his mind. But living was a field of grain blowing in the wind on the side of a hill. Living was a hawk in the sky. Living was an earthen jar of water in the dust of the threshing with the grain flailed out and the chaff blowing. Living was a horse between your legs and a carbine under one leg and a hill valley and a stream with trees along it and the far side of the valley and the hills beyond” (312-313 on the last moments of Sordo’s life during his last stand against advancing fascists before he is killed in a plane raid).

For Whom The Bell Tolls tells the true account of war far greater than mere fact or history: it presents the experience of a soldier in all its complexity. Robert Jordan is a multi-faceted man: he is anxious, confident, distrusting, steadfast, competent, sorrowful, determined, and yet friendly. He is both a lover and a fighter who experiences the great depths of love amidst the heart-pounding threat of war.

“You felt, in spite of all bureaucracy and inefficiency and party strife, something that was like the feeling you expected to have and did not have when you made your first communion. It was a feeling of consecration to a duty toward all of the oppressed of the world which would be as difficult and embarrassing to speak about as religious experience and yet it was authentic as the feeling you had when you heard Bach, or stood in the Chartres Cathedral or the Cathedral at Leon and saw the light coming through the great windows; or when you saw Mantegna and Greco and Brueghel in the Prado. It gave you a part in something that you could believe in wholly and completely and in which you felt an absolute brotherhood with the others who were engaged in it. It was something you had never known before but that you had experienced now and you gave such importance to it and the reasons for it that your own death seemed of complete unimportance; only a thing to be avoided because it would interfere with the performance of duty. But the best thing was that there was something you could do about this feeling and this necessity too. You could fight” (235, on the experience of war).

The question of death, namely what is a good and noble death, also looms large over the novel. Robert Jordan’s father had committed suicide, an act which he considers cowardly. He occasionally reflects on his troubled father throughout the novel. Robert Jordan recalls the story of a compatriot who requested he be shot instead of falling into the hands of the fascists. Instead, Robert Jordan values a man who ends his life fighting without surrender. And Robert Jordan is also contrasted with other characters in the novel, particularly Pablo, who has become cowardly and all-too-comfortable in his hidden cave while drunk in a bowl of wine. Sadly, Pablo’s fear of death has overcome his desire for virtue or honor, and even his own wife does not respect him. In contrast, El Sordo dies bravely in battle. In the end, we are led to believe Robert Jordan dies a good death, as well. Perhaps the most striking moment that discusses a noble versus ignoble death occurs when Pilar recounts the brutal killings of fascists in her town square. Some people go to their death bravely and without fear, while others are weak and cower before the crowd of people.

“‘If you have not seen the day of revolution in a small town where all know all in the town and always have known all, you have seen nothing…'” (106, Pilar sharing a horrific story of anti-fascists, including Pablo, who assassinate sympathetic townsfolk with the fascist cause, one by one. Some die nobly and willingly, while others die in disgrace and dishonor. It is a jarring but instructive scene).

In the end, Robert Jordan ends his life as an honorable man. After blowing up the bridge, and while running back into the mountains, Robert Jordan’s leg is horribly broken in an explosion. He is dragged up to safety by the others but he simply cannot carry on. Knowing his fate, he calmly develops a plan. He says goodbye to his lover, María, and tells Pablo, Pilar, and the others to press on without him. Hemingway dramatically leaves us with this scene in the end: a mortally wounded Robert Jordan waiting beside a tree, feeling his heartbeat against the pine needles on the forest floor, while a fascist cavalry unit turns the corner and Robert Jordan prepares to open fire.

“I have fought for what I believed in for a year now. If we win here we will win everywhere. The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it. And you had a lot of luck, he told himself, to have had such a good life” (467).

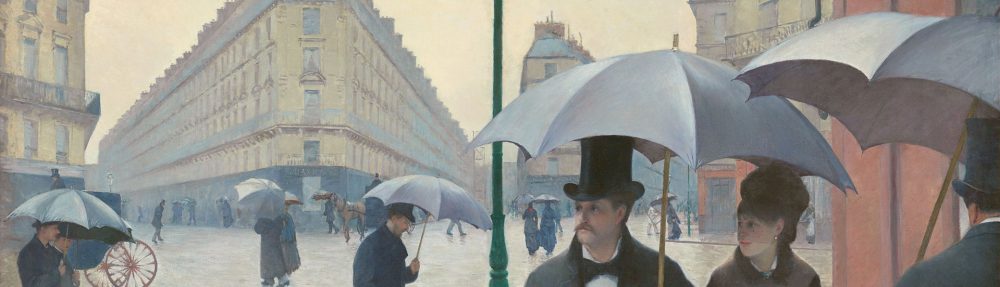

Ernest Hemingway was a lifelong lover of Spain, particularly the encierro in Pamplona. He was a supporter of the Loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War (the anti-fascists) -he served as Chair of the Ambulance Committee for the Medical Bureau of the American Friends of Spanish Democracy. He also publicly supported the Spanish Republic in 1937 when he produced an hour-long pseudo-documentary movie The Spanish Earth together with Jörg Ivens and John Dos Passos (read my review of the film here). Hemingway wrote the script and narrated the film (Orson Welles was originally slated too narrate the film). A beautiful technicolor film version of For Whom The Bell Tolls was released in 1943 (read my review of the film here). Hemingway was also a war correspondent reporting on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Association (NANA) between 1937-1938. He left Spain for the last time in 1938 and wrote a series of short stories about the Spanish Civil War before setting himself up at the Hotel Sevilla Biltmore in Havana where he began writing For Whom The Bell Tolls. His writing regimen began at 8:30am and continued until 2pm or 3pm, the same practice he had established when writing A Farewell to Arms.

After traveling in Cuba and Montana, he searched for a title for the novel, first turning to the Bible and Shakespeare, before discovering John Donne’s poem “For Whom The Bell Tolls” in the Oxford Book of English Verse:

“No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man

is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a

Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse,

as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor

of thy friends or of thine owne were; any mans death

diminishes me me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And

therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.”

The allusion to John Donne’s poem, which was originally published in 1624 from his presumed deathbed, points us to themes of isolation, death, and the need to belong. The Spanish Civil War offers Robert Jordan the chance to find fraternity and purpose in fighting the threat of fascism. If there is no greater love than for a man to lay down his life for his friends, then Robert Jordan finds his deepest love on the battlefield of central Spain. His life is an important piece of an intricate puzzle in a worldwide chain of being. The war in Spain is not an island, but rather a part of a broader global conflict set to explode with World War II. In For Whom The Bell Tolls, the idea of war comes to light as a harsh teacher, a bearer of unforgiving truth, a life-affirming cause of brotherhood and meaning in a meaningless world. Love and death have the power to unveil the hidden character of modern man, by testing his prudence, courage, temperance, and justice. War reveals to us the grandeur and also the limits of mankind.

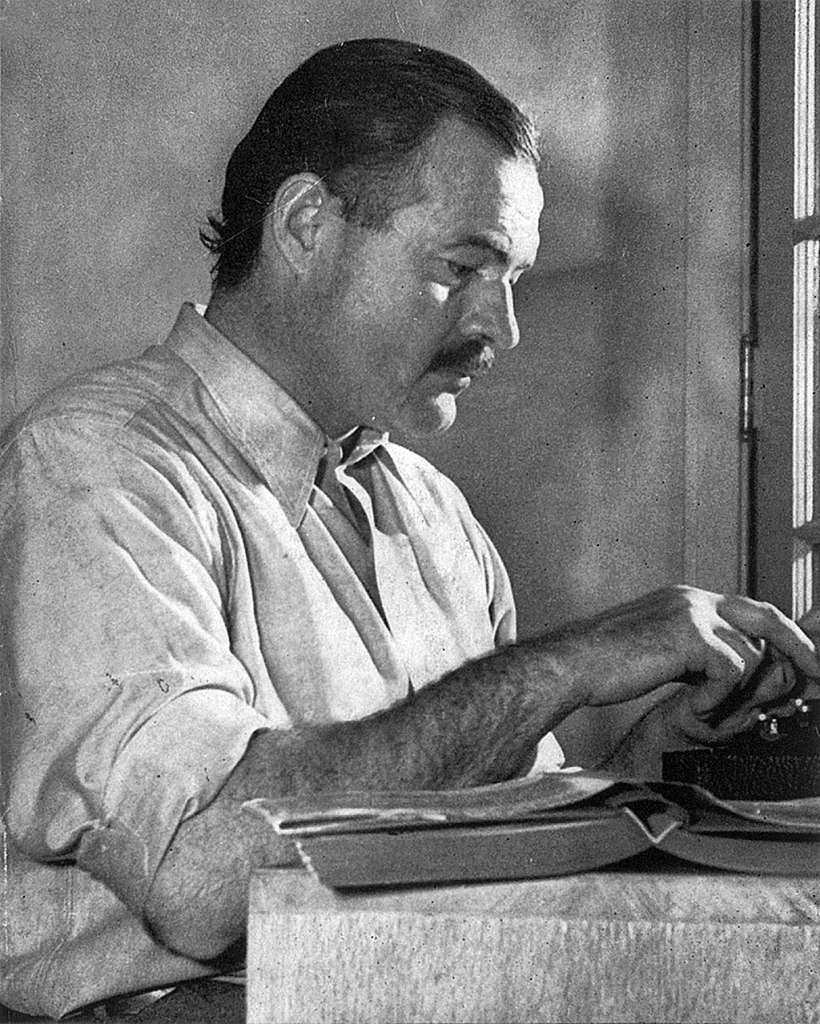

About Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) led a fascinating and storied life. He was born in Oak Park, Illinois, a small town outside Chicago. He cut his teeth writing as a journalist for the Kansas City Star in 1917. There, he built his signature writing and editing style: concise, direct, and honest sentences that tell the truth above all else.

During the outbreak of World War I, Hemingway became a volunteer ambulance driver for the Red Cross on the Italian front but was wounded and sent home. He married his first wife Hadley Richardson and moved to Paris where he joined a circle of post-war artists and critics: Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, and others. In Paris, Hemingway began writing his first collections of poetry and short stories. In 1926, he published his first modernist classic, The Sun Also Rises, a reflection of his years as an expat in France and Spain.

In the late 1920s, Hemingway returned to the United States and published his World War I novel, A Farewell To Arms. He had an affair and divorced his first wife to marry Pauline “Fife” Pfeiffer. He then moved to Key West and Cuba. While traveling widely throughout the world, he wrote books about bullfighting (Death In The Afternoon) and an account of big game hunting in Africa (The Green Hills of Africa). Hemingway had another affair and he left his wife for another woman -he remarried a third time, this time to Martha Gellhorn (he dedicated For Whom The Bell Tolls to Martha Gellhorn).

In the 1930s, Hemingway became an international reporter on the Spanish Civil War, which eventually spawned For Whom The Bell Tolls, and with the growing turmoil in Europe, he hand-delivered the novel manuscript to his publisher Max Perkins at Scribner’s in New York in July 1940 (the book would later be praised by two adversaries and American statesmen: John McCain and Barack Obama). Hemingway then hunted U-Boats in the Caribbean and reported on the European front in World War II. He remarried for the fourth and final time to Mary Welsh who remained with him until his death. In 1952 he wrote The Old Man And The Sea. Shortly thereafter, he won the Pulitzer in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in 1954. At the end of his life, Hemingway’s mental health had deteriorated, particularly after he received electroshock treatment. He killed himself by a self-inflicted shotgun blast in Ketchum, Idaho in 1961 -the same way his father had also died (and the way Robert Jordan’s father died in For Whom The Bell Tolls).

For my full notes on Ernest Hemingway’s life, click here.

To read my reflections upon reading The Paris Review’s famous interview with Hemingway (1958) click here.

Hemingway, Ernest. For Whom The Bell Tolls. New York, Scribner, 2003.

Click here to return to my survey of the Pulitzer Prize Winners.

Pingback: For Whom The Bell Tolls | Great Books Guy

Pingback: The Writer’s Endurance: The Old Man and the Sea | Great Books Guy