The rage, or menin (sometimes translated as “wrath”), of Achilles is the opening word of Homer’s Iliad and it bears crucial significance with respect to the remaining content of the epic. This opening word stands in contrast to the first line of the Odyssey, a text about a man, whose opening word is andra, meaning “man.” If we take the assumption, following from the title, that the Iliad is a book about the city of Ilium, why, then, do we find the rage of Achilles to be a central theme? Is there a connection between the godlike rage of Achilles and either the birth or destruction of the city? What is the rage of Achilles?

In Book I, the rage of Achilles finds its form as a result of Agamemnon ignoring the priest of Apollo, causing the god to send a plague to the Achaeans. Achilles, frustrated with Agamemnon’s tenuous leadership, publicly berates him. A competition then ensues between the two men, revealing an Achaean contest for the best of men –the most excellent among the warriors. Agamemnon believes himself to be the best of men because he rules the greatest number, and therefore he is deserving of the greatest goods. This belief causes Agamemnon to take Briseis, a prize rightfully won by Achilles, to claim her as his own. Achilles, however, believes himself to be the best of men because he is the greatest warrior. The power of his aggression instills fear among the Achaeans and Trojans alike. Since both men cannot be the best, there is need for justice. Therefore, the Iliad is a book which has a great deal to say about politics.

In a world governed by force and compulsion, war is redemption –a fierce and cruel teacher. Conflict offers the opportunity to gain honor, it is a demonstration of pride. In the narrative, Agamemnon commands his great soldiers to forcibly claim Briseis. Achilles initially intends to kill Agamemnon in response, but he is prevented by wise Athena. Instead, Achilles pursues a strategy of inaction. He knows that his deadly skills as a warrior are most valuable to Agamemnon and the Achaeans. Therefore, in order to assert his excellence, he withholds his sword and prevents his Myrmidon troops from entering the battle as punishment.

Achilles prays to his mother, the goddess Thetis, to turn the tide of war against the Achaeans. By actively not participating in the battle, a version of what might be called “civil disobedience,” Achilles ponders the question of returning home to the house of Peleus where a long and peaceful life awaits him. Long ago, a prophecy was made that Achilles could either remain in Troy and kill Hector only to die shortly thereafter, or instead, he could return home to a long but forgotten life. Achilles makes a choice between having a glorious and memorable death, or else domesticity and anonymity. The character and quality of a hero’s death is paramount, and being remembered is the only chance of glimpsing enduring life.

Achilles’s rage, in Book I, is a decisive factor for the Achaeans. By offending the honor of Achilles, Agamemnon seals the fate of the Achaeans. Achilles’s great wrath is the only impulse that can overcome even the will of the gods, though it cannot escape his fate. Rage, the deep desire for vengeance, is a fundamentally human impulse. Like a wild untamed beast, Achilles struggles to force himself to return home, yet he refuses to return to battle as it would require confirmation of Agamemnon’s excellence. He is trapped in a stasis.

Although there is an attempt made by Odysseus and a group of Achaean leaders in Book IX to offer to return Agamemnon’s stolen gifts to Achilles, and thereby persuade him to rejoin the battle, this request ultimately fails. Achilles remains firm, he will not be persuaded. Achilles privately mentions to Patroclus that he will not remain wrathful forever, only until the Trojans have beaten the Achaeans all the way back the hulls of their ships. He mentions this fact upon taking “pity” on his friend Patroclus, with tears streaming down Patroclus’s face (Book XVI 1-19). As a warrior, Achilles is moved great passions. Achilles allows Patroclus to rejoin the battle with the Myrmidons because young and impressionable Patroclus has been emotionally moved to action by the words of Nestor when visiting the Achaean front lines. This makes Patroclus’s death all the more devastating for Achilles. Upon Patroclus’s tragic death, Achilles redirects his anger instantly.

“…the spirit within does not drive me

to go on living and be among men, except on condition

that Hector first be beaten down under my spear, lose his life

and pay the price for stripping Patroclus, the son of Menoitios” (Book XVIII, 90-93).

As a man of deep passions, Achilles nevertheless wishes for all strife and anger to dissipate. Due to the death of Patroclus, Achilles will actively forgo (rather than forgive) the past transgression of Agamemnon and refocus his rage on Hector. Notably the rage of Achilles, a natural outward impulse, is initially directed inward –toward the Achaeans. However, once his great passions are drawn externally toward Hector, the killer of Patroclus, Achilles immediately relinquishes his rage and peaceful comity resumes among the Achaeans. Achilles is the archetypal warrior, and can only direct his anger toward one kind of enemy: internal (against the city) or external (toward an enemy of the city). It is, therefore, in the interest of the city to see the warrior treated justly internally, but unjustly externally –that he faces an enemy. In this way, the warrior and his unbearable rage, helps to reinforce the city as a cohesive whole.

However, the rage of Achilles is vengeful, and it is therefore reactionary. He is driven toward revenge, or perhaps requital. Take, for instance, the stripping of Achilles’s armor from the body of Patroclus in Book XVI, which is an unforgivable act in Achilles’s eyes. In order to claim his vengeance on Hector, Achilles mercilessly slaughters his enemy, and with his dying words, Hector tries to persuade Achilles not to leave his body for the dogs, but stubborn Achilles refuses –he has a “heart of iron” (Book XXII, 288-361). His interaction with Hector stands in stark contrast to other Trojans v. Achaean battles, which are predicated on mutual respect. Achilles, instead, yearns to demoralize and defile the body of Hector. His rage transcends the limits of law and custom in battle.

Finally, the last point to be made in an examination of Achilles’s rage, occurs in Book XXIV, the final book of the Iliad. Priam, king of Ilium, comes to Achilles to plead for his son’s body to make a proper burial. Notably, throughout the text, only two people successfully persuade Achilles and both occur in weepy moments of lament. The first, as discussed earlier, is the weeping plea of Patroclus to rejoin the Achaeans and help push the Trojans back. The second, however, occurs when King Priam approaches Achilles, physically takes his hand, and beckons him to recall his own father, Peleus. How is it that Achilles allows himself to be persuaded during these impassioned moments, but refuses to Odysseus or Ajax? Achilles, the archetypal warrior, does not have a particularly strong capacity for reason. Instead, he allows his heart and his wild passions to overpower him. In order to persuade the warrior, one must physically regulate his emotions. His only weakness is in what exposes his vulnerabilities, whether it be his heel or his deep affection for a friend or a father. In both cases his heart is softened. Achilles is vulnerable to pity and sorrow. However, this great pity is intimately connected to his deep sorrow –the warrior must be made to feel more than to discourse. Still, a problem persists in the need for the city in possessing warriors who take honor and pity among their own stock, yet feel rage toward the city’s enemies. For Achilles, this rage takes its greatest form in reaction to the death of an intimate friend.

The warrior, unlike the magistrate or king, is dangerous. His untamed passions are the fruit of chaos, both within and without the city. Therefore a wise leader, like Nestor, who compels the spirit of the young Patroclus, can wisely redirect Achilles’s rage by foreseeing the death of his friend. It is far better that the great warrior’s rage is channeled outward, rather than inward, in order for the city to endure.

For this reading I used the Fagles and Lattimore translations.

The ‘like’ button is not enough! This is awesome:

“However, this great pity is intimately connected to his deep sorrow -the warrior must be made to feel more than to discourse, yet the problem lies in the need for the city to have warriors who take honor and pity among there own stock, yet feel rage toward the city’s enemies. For Achilles, this rage takes its greatest form in reaction to the death of an intimate friend.”

So beautifully expressed and so perceptively comprehended!

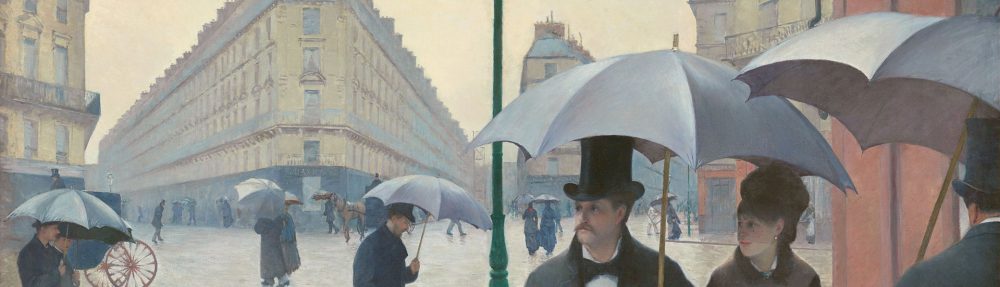

I hope you will allow me to repost this on my site http://theshieldofachilles.net as your first guest post. With your permission, I would love to use public domain images of historical fine art to illustrate it as well.

Please let me know if you agree!

LikeLike

Hi Kathleen,

Sure go for it!

-John

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful, John, thanks very much. I’ll send you a link when it’s ready!

LikeLike

Hi John, Are you okay with me publishing your name as the author of your guest post on my site? Please let me know either way. If you are, you can reply by email with your last name and any bio info you’d like to include. Since your post fits so well into the flow right now, I’m hoping to publish it next, either on Tues, June 13 or Friday, June 16. Thanks again! – Kathleen

LikeLike

Interesting read! Having re-studied this matter closely, I feel I must come to a different and surprising conclusion. There may be method is his rage.

firstly, I see Achilles refusal to defer as his way of standing up for standards and justice, to forge order in a world of royal caprice and arbitrariness. If it was simply power and wealth he wanted, then with his supernatural fighting skills, he could easily have displaced Agamemnon.

If Achilles had simply allowed Agamemnon to take Briseis away without a terrible display of protest, he would have become an enabler of tyranny and incompetence, which hurts the whole world and posterity. If he had been readily accepting of Agamemnon’s compensation, that would just lead to settlement culture where the high and mighty can repeatedly steal from subordinates and throw a coin back every now and then.

Thus, by pulling a high profile Atlas Shrugged, Achilles benefitted the little man everywhere by leveraging his demigod abilities to create an example of justice that will serve as a reminder to contemporary and future leaders to respect the property and women of their subjects, to show decisive competence in leadership and war (i.e. don’t cover up plague cause). Agamemnon had no right to be so greedy and incompetent when the whole city and lion’s share of loot would be his eventually.

Off course, looting, slavery, collective responsibility and bloody loss of life is unacceptable nowadays. However, back then, it was unfortunately a thing. So we must analyze it from the standards of the time.

As for the wrath and blood lust, I feel we must look at this from the perspective of hospitality and brotherhood and filial trust. In those unstable times, the only security was family and the social fabric (i.e. trade, commerce, civilization) was welded together by hospitality. Paris violated this by seducing Helen and stealing Menelaues’ fortune while a guest. If this went unpunished, then civilization would break down. They didn’t have hotels or vast police forces and social services back then; food, shelter, security was provided by households. Hospitality to them is just as important as the banking system is to us.

Thus Achilles actions after Patrolcus’ death and his general brutality towards the Trojans was to set an example so awe inspiring that people in the future would think twice before violating the code of hospitality and or enabling others who do so.

We should also note that Achilles does fully respect his mother’s orders and was hospitable to King Priam, giving him protection and consideration. Moreover, he did not neglect funeral rites but held honorable funeral for Patroclus and got 12 days truce so that Priam could hold a splendid funeral for Hector (despite the fact that they should have forced Paris to return Helen and the stolen money promptly to Menelaus).

Thus, I feel that despite the crudeness that his actions may appear to give, he is selfless in that he forfeits using his strength to live a life of hedonistic tyranny, but instead uses it as leverage to force justice, excellence, competence and order, thus benefitting civilization at large. So he was kind of like an unwritten constitution. And that is why he is remembered as a Hero. Not one we need today, but one in those brutal times.

LikeLike

This will help with the essay that I am writing about the Illiad!

Thank you!

LikeLike